Ghost Tide

The Ghost Tide

Rob La Frenais, 2018

“You never know what the river will bring on the next tide. Nor do you know what secrets it holds, never to be revealed again.” That was the possibly fictional character of ‘Maeve’ of the ‘Redriff Society of Thames Sifters’ as described by Portals of London – a blog which made a impact earlier in the decade with the cleverly- woven tale of the ‘time anomaly’ in the Woolwich Foot Tunnel. This tunnel was in actual fact closed for repairs in 2011 and the work was delayed for unexplained reasons. Portals of London does an excellent job of weaving fiction and psycho-geography, to mess with our minds in the account of an anonymous worker on the foot tunnel at the time: “I was one of the first ones to experience it. We were working from both ends, as it were, and had tents on both sides of the river. It was pretty basic, if you wanted something from the other side, you just had to walk it through the tunnel. Anyway the foreman’s on the other side and he radios to ask me across. So I walk through the tunnel – the ‘long walk’, we called it, funnily enough – and it’s slightly spooky because no one else is down there, they’re all working on the lift shafts, and I get up the other side, find the foreman, and his eyes nearly pop out of his head. Says he only radioed like a minute ago and how did I get there so quick?”

This rather convincing account of how time sped up under the Thames was revealed to be the anonymous creative work of a former cycle courier in an interview by the Guardian. “A lot of people obviously don’t believe in inter-dimensional portals, so they didn’t think the stories were real. But they weren’t sure if the person writing it thought it was real.” The same spirit of creative ambiguity imbues the curatorial work of Sarah Sparkes and Monika Bobinska, who have, in the exhibition The Ghost Tide gathered a diverse and prolific flood of artists, shamans, mediums and other entities to the edge of the Thames to investigate the hauntological possibilities of this great tidal river that has inspired writers from Dickens to Ian Sinclair, the scene of disasters

like the Marchioness or the less-known sinking of the the Princess Alice with over 750 dead, which sweeps inexorably through this massive, numinous, money-laundered city. There is something specific about big, sprawling, cities that have tidal rivers flowing straight through them, dividing North and South. As a Thames tideway rower myself I have sat, balancing the boat in the middle of the river at high tide and felt the massive ebb and flow underneath me, bouncing about in those deep murky waters which have drawn down quite a few lives beneath them. The exhibition is, appropriately, just near to the Thames flood barrier. Sarah Sparkes: “The barrier is just outside, to hold back the flood tide -but the ghosts still get through!”

The Thames is indeed a spooky, unsettling river. Monika Bobinska: “ I think of things like the Marchioness disaster or Malcolm Hardee’s drowning or that couple on a date on the boat or the Westminster bridge attack which all seem to bring that ancient frightening, unsettling, mythical aspect back to the now, in contrast to the Thames as a confident gateway to a mighty modern city with the Queen sailing down it.” Sarah Sparkes adds: The Thames has always been a major conduit for the movement of people and goods, bringing the other or the alien from overseas. It is a source of life – water – many people have and still live along its banks. It is also a potential source of death, many people have drowned in the Thames”.

Artist Laura Marker, in a new work, focusses on drowning in those unsettling watery depths in 10 Days and Nights – thinking about the trope of the ‘drowned woman’ in works that are focussing on the river Thames as the location for the scene of tragedy; George Frederic Watts’ painting Found Drowned, Thomas Hood’s poem The Bridge of Sighs, and prints created for George Cruickshank’s book, The Drunkard’s Children. Works that depict The Drowned Woman are heavily romanticised visions of fantasy, with their all-too-familiar tragic subjects; youthful, beautiful, heavy with the symbolism of the ‘fallen’ woman”. Her work developed through research into both nineteenth century artistic responses, and journalistic writings featuring Thames side suicides, seeks to bring a more personal voice to The

Drowned Women, uncovering their stories and ‘ghosts’ lost to time and lost to the Thames”. Davies, Monaghan and Klein, Heidi Wigmore and Anne Robinson also refer to drowning and losses at sea.

This exhibition emphasises the power of objects to be imbued with empathetic energy, including things found floating in the Thames, like flotsam and jetsam. Charlie Fox has appeared in the persona of Sailor Forbes who, “as a long serving seasalt, has channelled the spirit of whalers, traders and the unrecuperated naval expeditions, that haunt the foreshore…He also hopes to be able reappear within the locale, to guide other lost souls and curious through the shipwrecks and detritus of Woolwich allowing the public to navigate the area as a spirit zone, filled with the flotsam and jetsam of a derelict limbo time”. Charlie Fox is the instigator of Inspiral London – a collective spiral psycho- geographic walk which spirals from Nelson’s column to the M25.

Diane Eagle’s work is inspired by ritual, emotional and spiritual investment in objects, healing and power, and the historic resonance within places. Her objects in Pipes is inspired by the Tooley Street/Joiner Street tobacco pipe found during the archaeological work carried out prior to the current development of London Bridge train station. These pipes mark the trade, industries and history particular to the London Bridge and Southbank area at the time when the station first opened in December 1836 – pipe maker, railway worker, coaching inn keeper, wool merchant, dissenter, Guy’s Hospital nurse, leather manufacture, hat maker, St. Olave’s Grammar School mistress, river boatman, rope maker, hop picker. Jane Millar also is working with significant objects – in her case she is inspired by Dr John Dee’s scrying mirror in the British Museum. Obviously it would be impossible to get a loan of this, but her ceramic objects act similarly as ‘ghost vessels’ where the spirit is is “trapped within an object, and revered, or feared and abandoned”. Like artist/ curator Sarah Sparkes, she is also organising an exhibition coming soon, New Doggerlandreferencing that imaginary domain in the North Sea.

While The Ghost Tide reflects many ghostly obsessions with the tidal Thames, it extends further out into the Estuary and out to the North Sea, where some of these artists live, forced out of their studios in London by rising prices. These hinterlands, particularly places like Thanet and Canvey Island have their own very specific psycho- geography. Matt Rowe, for example, whose Bad Omen is the cover image for this exhibition, making a mummers or ‘gilly’ suit referencing the horror movie ‘The Omen’ and also hints at the way coastal gentrification, which as Sarah Sparkes puts it “tries to exorcise the ghosts of the past – but they still get through the net curtains and the kitsch plastic windmills of seaside vernacular.”

Heidi Wigmore, based in Leigh on Sea, in Prayer Flags is inspired by the leather shoes recently recovered from the wreck of the HMS London, with their powerful and intimate human imprints and which evoke the historic movement of people, often perilous, on the Thames and in and out of the estuary. Sarah Trillo, another estuary explorer, explores ancient landing sites in Thanet and celebrating the liminality of the tide which exposes these sites fleetingly. Apparently it was believed these liminal tidal sites were considered poisonous to snakes. Further afield, Kio Griffith, in Yugawara Elegy, explores remnants of a Japanese ghost town, recreating lost Inns, hot springs and arcades that had vanished.

Miyuki Kasahara has used objects found and collected along the Thames foreshore to explore a Japanese Noh play Utoh about the ghost of a man who was once a seabird hunter. Kasahara: “A hunter imitated the sound of the parent in order to catch their young. In retribution for cruelly tricking so many, he was sent to hell when he died. In hell, Utoh became phantom- birds and continuously tormented him. He learnt that the birds he killed loved their families as much as he loved his own family. The parent birds weep tears of blood upon seeing their young taken, and hunters must wear large hats and raincoats as protection from falling tears, the touch of which causes sickness and death. In contemporary society, we don’t often kill seabirds directly like the hunter. However, almost all the seabird population has declined because of marine pollution. “

As well as the found objects she has work tethered to a post on the foreshore, near the abandoned Mersey Ferry – the nearby ’Ghost Ship’ the Royal Iris – a past site for artists actions – so that it floats in the Thames with the rising and falling tide. “creating a gateway to the sea in order to evoke this ghostly tale”. There are also performances taking place around this wonderful vessel which haunts the Thames Barrier, notably Gen Doy’s Only Death (After Pablo Neruda) and referring to the deaths of migrants in the Mediterranean and in refugee camps.

Katie Goodwin is also influenced by seabirds in her digital animation of ‘Martha’, the world’s last passenger pigeon who died in September 1914 at Cincinnati Zoo. According to the artist she was the last of her kind, despite once being the most abundant bird in the world, with an estimated population of 3 to 5 billion. It is said that when a flock flew over, the sky would turn black for several minutes. Despite their abundance, it is thought the North American bird species was lost due to overhunting and destruction of its natural habitat.

More wildlife enters The Ghost Tide with Calum Kerr: “There have been sightings of a Ghostly White Cachalot (or Sperm Whale) by the Thames at Enderby’s Wharf, Greenwich and near the estuary at Gravesend. The unfortunate Bottle-nosed (Thames) Whale of 2006 passed both of these sites and Woolwich, on the way to its demise. Recently, the Ghostly Whale has been sighted near Thames-side and along the Thames Barrier path, lamenting whales lost in its waters. Sperm Whales communicate through echolocation, clicking noises that are the loudest sounds emitted by any animal – 230 decibels under water, equivalent to 170 decibels on land. The eerie sound of this communication with the living skirts the shorelines. This whale is beckoned by the spirits of the whalers and the destroyed industrial heritage of the Thames”.

Moving back to objects, many artists have been influenced by Nigel Kneale’s (Quatermass and the Pit) 1972 television play The Stone Tape, which reflected a growing interest in the idea that objects or building could contain ghost ‘recordings’ or voices generated by

traumatic events in the past. Sound artist Graham Dunning is no exception “I found a stone on the bank of the Thames which was similar in size to a cassette tape, so made an edition of copies of it. The original tape (master) is exhibited alongside one of the copies”. Another soundwork, by Neale Willis, also inspired by the history of psychical research, incorporates a ‘spirit trumpet’ of sorts, “metaphorically rising and floating around the room emitting ‘spirit voices’. As the machine performs its ‘trumpet séance’ voices are summoned telling stories of what is, what was and what has never been”. He is interested in the notion of Arthur Koestler’s ‘Ghost in he Machine’ through a technological seance, creating conflict between what enters the machine and what leaves it.

The Ghost Tide coincides not only with Halloween but also the Mexican Day of the Dead. Sarah Doyle , in her workshop and exhibit celebrates the famous object La Pasqualita, the so-called ‘corpse bride’ in the shop window of a bridal wear supplier in Chihuaha, Mexico. Millions flock to see this mannequin, which is reputedly the actual embalmed body of the shopkeeper’s daughter, bitten by a black widow spider. Sarah Doyle: “The one certainty in life that makes us equal is that we all die – no matter how rich or poor you are, you cannot avoid this.”

The human flesh, alive or dead, is also explored by Andrew Ekins In his painting, taken from radiological imagery of the body – ”the core subject is the lustre of human presence, an allusion to the materiality of a fleshy body of land, a crumpled landscape of the human condition. It engages with the idea of an embodiment of the human stain, the shadow between forgetting & remembering, and the ghost-memory of physical and emotional stigma. The imagery recalls a shroud with trace elements of a biology imprinted on a mapped topography, condensing the image of an intestinal tract & the snaking route of a riverbed. What is seen is an allusion between a body of land and a body of experience, the evocation of presence and place looking at the influence of transient presence upon habitat what is done and what is remembered, what is left behind.”

Mortality, leading out to the Thames, is explored by Toby McLennan in this evocative project about her father building a solar boat to cure himself, like a shaman. For this work she has built a ‘solar boat’ with the shape of a woman’s body (hers) within it, sailing through the mist, connecting to the shamanic belief that illness occurs when a person’s soul has wandered away, the shaman utilises the ship to sail out and retrieve the missing soul. She says “My father became ill with cancer and a brain tumour. He was depressed. He wouldn’t eat. He spent his days sleeping. Then one day he woke up and, struggling to sit up, he declared, ‘I have to build a boat.’ Knowing that my father couldn’t lift a hammer, my family shrugged off his proclamation as part of some delirium. However, I became convinced that my father, like a shaman, was trying to build a solar boat to save his life My father survived that immediate ordeal. In my work, Canoewoman, a canoe and I are one in the same. It was created in thanks to my father for showing me that, when need be, we are all able to sail out and retrieve our lost soul.” The paintings of Miroslav Pomichal also reference the boat as a metaphor for haunting with the story of a maid who is chased by the ghost of Bratislava along the Danube, in a metaphor for the fluidity of faith, nationality and geography in Central Europe.

There are some practising shamans alongside the artists here. Kate Walters describes the dream that caused her to make the work she created in Shetland, with Rorschach-like colours: “I had a big dream where I saw myself in a disembodied uterus, floating in space. The next day I felt extremely disorientated, and in the days that followed, I tentatively began to work with the images from my dream, and to write about them. Everything I saw and experienced on Shetland helped with this process. I experienced a profound change in my working practice, and the way I applied materials. All the ghosts of my past (lives) came into my work, and the ghosts or subtle beings I felt around me. I worked with an Arctic tern I’d found, also a lamb’s face on a hillside, with tiny blue eyes still intact. Subtle bodies, archaic sensing antennae, energetic wombs and the slipping into the bodies of other creatures became part of my working field.” Shamanic paintings also feature in

the trippy visualisations of David Leapman, to guide the viewer on their life’s journey toward the realm of the dead.

Mary Yacoob returns to the ambiguity of the Woolwich foot tunnel at the start of this essay with her drawings which try to evoke the imaginary (or not) time anomaly in the tunnel. Sarah Sparkes – also exhibiting The GHost Library and The Ghost Formula – which I curated at FACT Liverpool and the National Taiwan Fine Art Museum says about her experiences in Taiwan: “When I asked people if they believed in ghosts the majority would resolutely confirm that they did. However, when asked if they believed that the existence of ghosts could be proven through scientific means they were equally clear that it could not. It does not matter if ghosts’ existence can be proven, what is of interest to me is that they exist in our cultures – the living need ghosts, the living make ghosts”. I think this logic can equally be applied to the creative urban myth of the time anomaly in the foot tunnel.

Finally – do the curators think ghosts exist? Sarah Sparkes: “I have had encountered ‘ghosts’ during grief hallucinations, hypnopompia and sleep paralysis. In these conditions of mind, I have seen things that appear to have initially manifested from the external material world, but which I know cannot be there. A phenomena of the mind, they rapidly recede when full cognition returns. These visions haunt me, the dead, as yet, have not.” Monika Bobinska answers by relating her experience to London itself: “I also feel a bit like a ghost myself when I visit parts of London or elsewhere where I used to go, and I find them changed, and can visualise/superimpose myself and friends etc. there in the past. I feel invisible, as I am experiencing something quite different from the people who are going about their habitual activity”. Or, as Patrick Wright puts it in his text greeting the exhibition visitor “Something’s Not Right”.

The Ghost Tide also reminds us that here is another kind of ghost haunting London – the ghost property. The overblown, over-financed, over-priced edifice of London, with its hundreds of thousands of empty

properties bought and sold by the offshore underworld of international intrigue, tax havens and dirty money, bracing for the ill winds of Brexit, may crash like the Tower of Babel, but the magnificent Thames will ebb and flow as it has always done, bringing back and forth with its ghosts, myths and drowned souls for eternity.

Rob La Frenais is an independent curator. www.roblafrenais.info

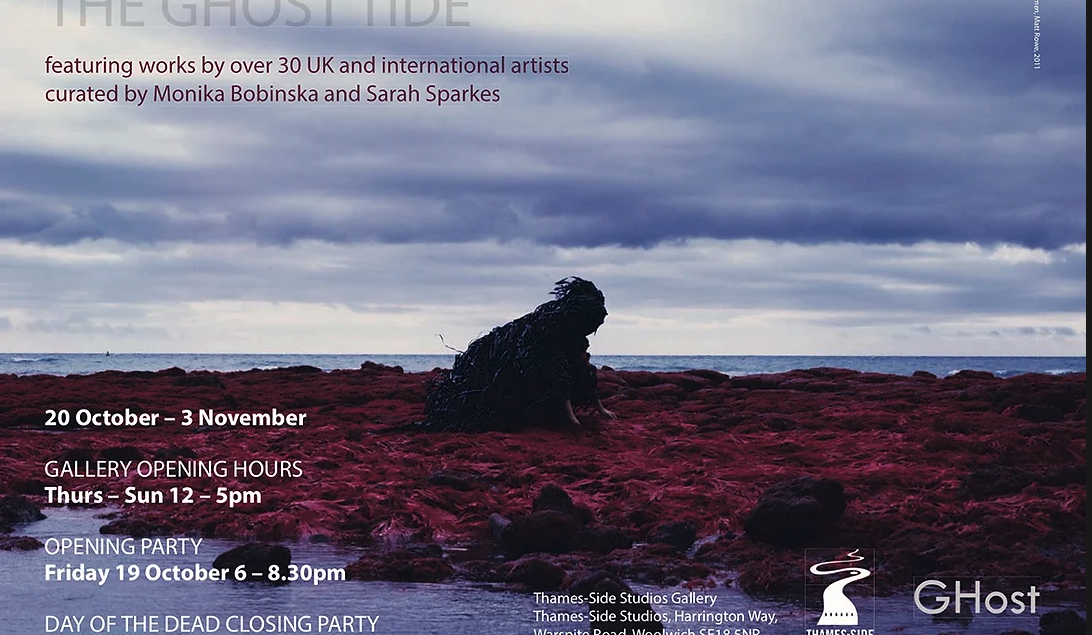

THE GHOST TIDE

curated by Monika Bobinska and Sarah Sparkes

Thames-Side Studios Gallery, Thames-Side Studios, Harrington Way, Warspite Road, Woolwich, SE18 5NR. www.thames-sidestudios.co.uk

EXHIBITION DATES 20 October – 3 November GALLERY OPENING HOURS Thurs-Sun 12pm – 5pm OPENING PARTY Friday 19 October 6pm – 8.30pm Gen Doy performance 7.30pm

The Ghost Tide – coinciding with the festivals of Hallowe’en, All Souls and the Day of the Dead – takes as its starting point the perspective that ghosts exist as an idea, or as part of a belief system, across cultures, across national borders and throughout recorded history. Most languages contain words to describe the ghost, spirit or immaterial part of a deceased person. Often, these words – like the type of ghost they describe – have traversed borders and been assimilated across cultures.

The exhibition, situated next to the Thames Barrier in South-East London, evokes ghosts as a migratory tide, washed up along the shore of the Thames their historical baggage in tow. It also explores the presence of artists in this part of London, as a migratory tide of creative flotsam and jetsam which ebbs and flows as the city gentrifies and develops.

Featured works include sculpture, installation, film, sound, performance and wall based works. The exhibition will include installations and outdoor interventions, as well as public events.

The Ghost Tide features works by over 30 UK and international artists.

Artists featured: Andrea G Artz, Chris Boyd, Davies, Monaghan & Klein, Gen Doy, Sarah Doyle, Graham Dunning, Diane Eagles, Andrew Ekins, Charlie Fox, Katie Goodwin, Kio Griffith, Miyuki Kasahara, Calum F Kerr, Rob La Frenais, David Leapman, Liane Lang, Toby MacLennan, Laura Marker, Joanna McCormick, Josie McCoy, Jane Millar, Output Arts, Miroslav Pomichal, Brothers Quay, Anne Robinson, Edwin Rostron, Matt Rowe, Sarah Sparkes, Charlotte Squire, Sara Trillo, Yun Ting Tsai, Kate Walters, Patrick White, Heidi Wigmore, Neale Willis, Mary Yacoob, Neda Zarfsaz.

About the Curators: Monika Bobinska is the director of CANAL, which organizes exhibitions and art projects in a variety of settings. She is the founder of the North Devon Artist Residency. Sarah Sparkes is an artist and curator. She leads the visual arts and creative research project GHost (initiated in 2008), curating an on-going programme of exhibitions, performances and inter-disciplinary seminars interrogating the idea of the ghost.