Dark Harvest

Dark Harvest

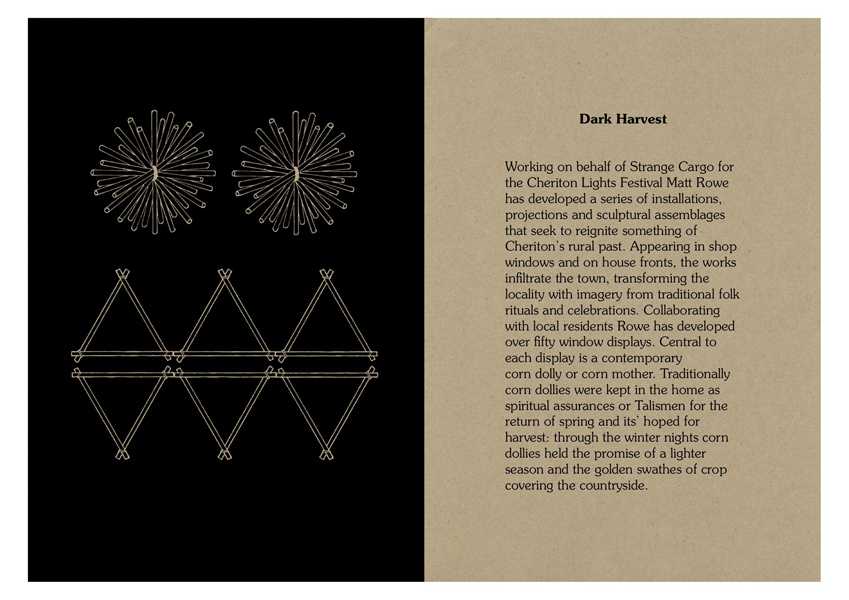

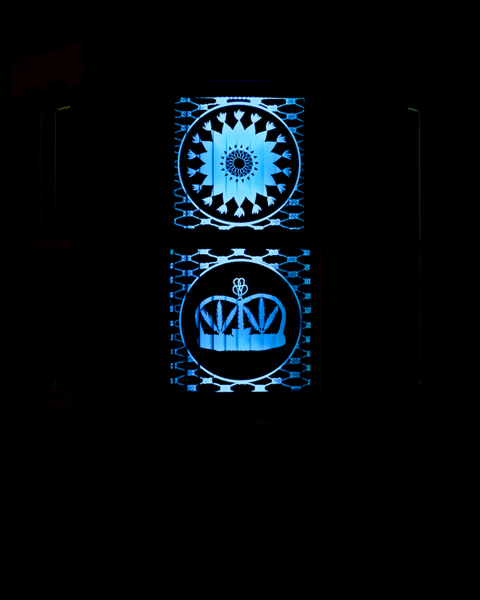

Working on behalf of Strange Cargo for the Cheriton Lights Festival Matt Rowe has developed a series of installations, projections and sculptural assemblages that seek to reignite something of Cheriton’s rural past. Appearing in shop windows and on house fronts, the works infiltrate the town, transforming the locality with imagery from traditional folk rituals and celebrations. Collaborating with local residents Rowe has developed over fifty window displays. Central to each display is a contemporary corn dolly or corn mother.

Traditionally corn dollies were kept in the home as spiritual assurances or Talismen for the return of spring and its’ hoped for harvest: through the winter nights corn dollies held the promise of a lighter season and the golden swathes of crop covering the countryside. Constructed from the last crop of an annual harvest the corn dolly was believed to house the spirit of the corn, John Barleycorn, who would become displaced once the crop was cut.Keeping the spirit in a decorative figure, it was perceived to remain safe until the coming of the new crop. When spring returned the cared-for corn dollies were ploughed into the first furrow of the new season, returning the spirit of the corn to its home in the fields and ensuring a successful crop. In rural England the fate of a community was often dependent upon the success or failure of the annual harvest. As such, celebratory rituals were developed to insure abundance in the coming season.

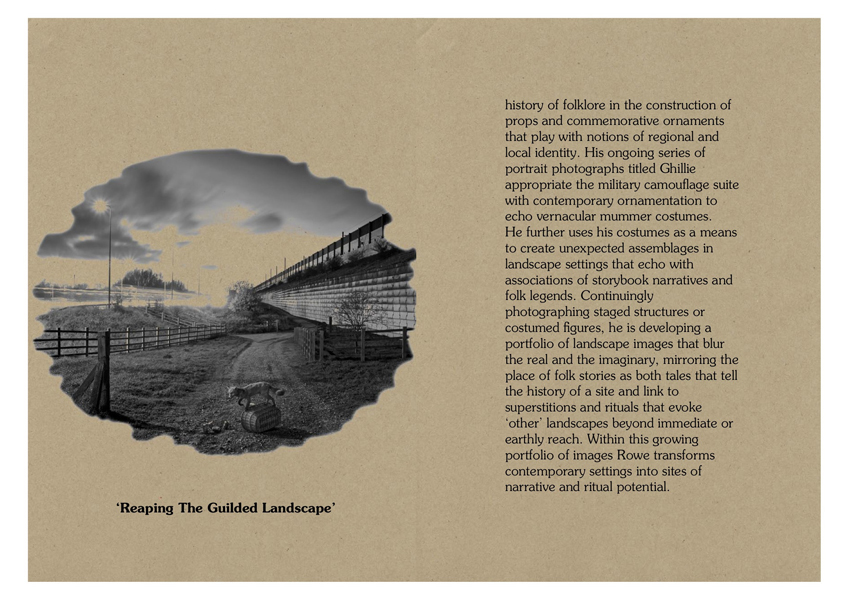

Dark harvest explores a history of rural rituals and superstitions linking the contemporary Cheriton Lights celebration to the county’s past. The use of the corn dolly resonates with Rowe’s wider practice, often drawing upon a history of folklore in the construction of props and commemorative ornaments that play with notions of regional and local identity.

His ongoing series of portrait photographs titled Ghillie appropriate the military camouflage suite with contemporary ornamentation to echo vernacular mummer costumes. He further uses his costumes as a means to create unexpected assemblages in landscape settings that echo with associations of storybook narratives and folk legends. Continuingly photographing staged structures or costumed figures, he is developing a portfolio of landscape images that blur the real and the imaginary, mirroring the place of folk stories as both tales that tell the history of a site and link to superstitions and rituals that evoke ‘other’ landscapes beyond immediate or earthly reach. Within this growing portfolio of images Rowe transforms contemporary settings into sites of narrative and ritual potential.

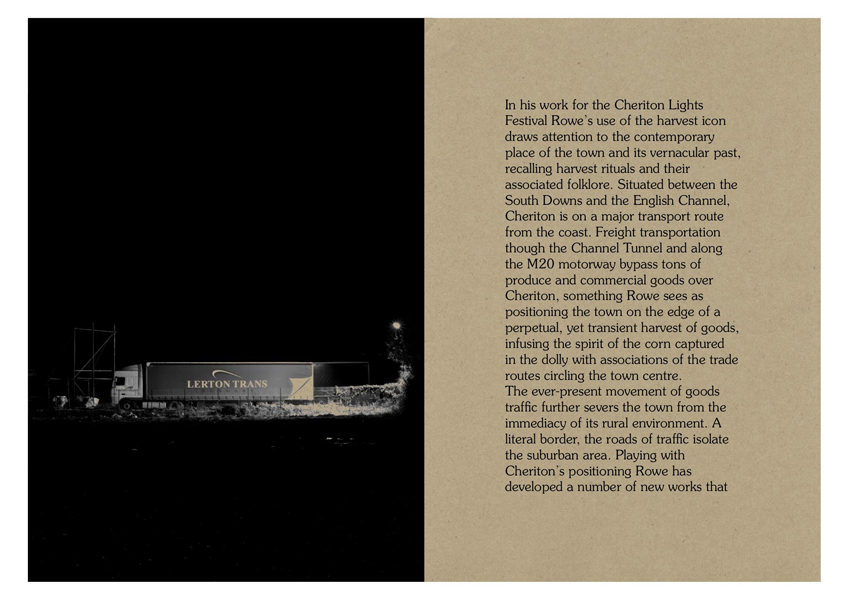

In his work for the Cheriton Lights Festival Rowe’s use of the harvest icon draws attention to the contemporary place of the town and its vernacular past, recalling harvest rituals and their associated folklore. Situated between the South Downs and the English Channel, Cheriton is on a major transport route from the coast. Freight transportation though the Channel Tunnel and along the M20 motorway bypass tons of produce and commercial goods over Cheriton, something Rowe sees as positioning the town on the edge of a perpetual, yet transient harvest of goods, infusing the spirit of the corn captured in the dolly with associations of the trade routes circling the town centre.The ever-present movement of goods traffic further severs the town from the immediacy of its rural environment. A literal border, the roads of traffic isolate the suburban area. Playing with Cheriton’s positioning Rowe has developed a number of new works that quietly interrupt the town centre, bringing imagery of the rural South Downs landscape into the heart of the town, crossing the physical border of bypass and motorway.

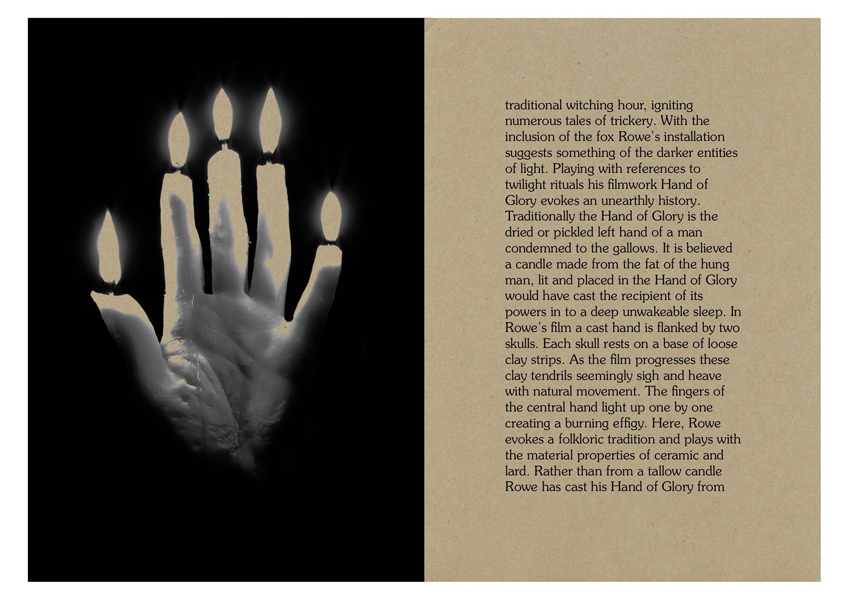

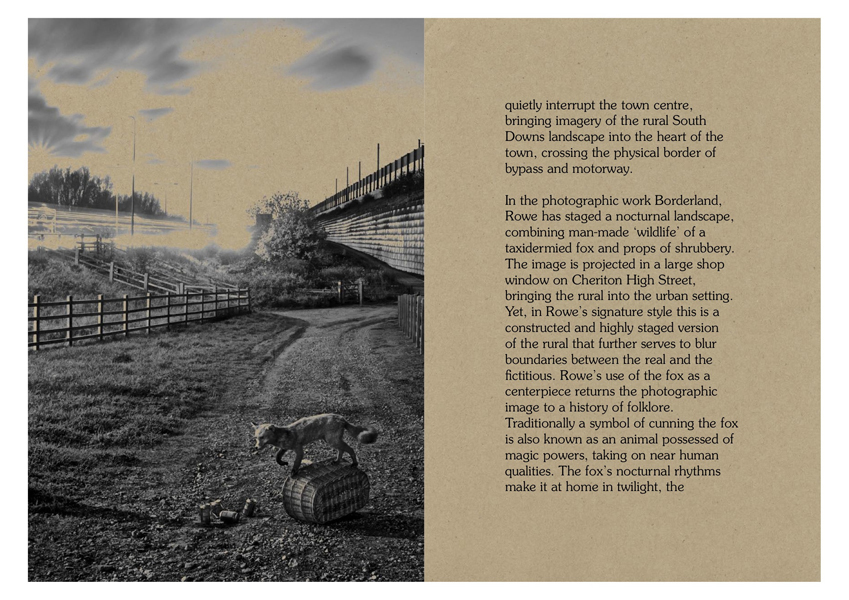

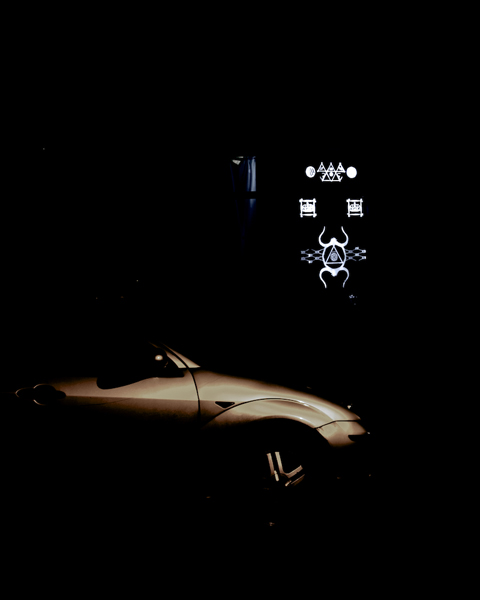

In the photographic work Borderland, Rowe has staged a nocturnal landscape, combining man-made ‘wildlife’ of a taxidermied fox and props of shrubbery. The image is projected in a large shop window on Cheriton High Street, bringing the rural into the urban setting. Yet, in Rowe’s signature style this is a constructed and highly staged version of the rural that further serves to blur boundaries between the real and the fictitious. Rowe’s use of the fox as a centerpiece returns the photographic image to a history of folklore. Traditionally a symbol of cunning the fox is also known as an animal possessed of magic powers, taking on near human qualities. The fox’s nocturnal rhythms make it at home in twilight, the traditional witching hour, igniting numerous tales of trickery. With the inclusion of the fox Rowe’s installation suggests something of the darker entities of light. Playing with references to twilight rituals his filmwork Hand of Glory evokes an unearthly history. Traditionally the Hand of Glory is the dried or pickled left hand of a man condemned to the gallows. It is believed a candle made from the fat of the hung man, lit and placed in the Hand of Glory would have cast the recipient of its powers in to a deep unwakeable sleep. In Rowe’s film a cast hand is flanked by two skulls. Each skull rests on a base of loose clay strips. As the film progresses these clay tendrils seemingly sigh and heave with natural movement. The fingers of the central hand light up one by one creating a burning effigy. Here, Rowe evokes a folkloric tradition and plays with the material properties of ceramic and lard. Rather than from a tallow candle Rowe has cast his Hand of Glory from everyday supermarket lard, re-framing the ancient ritual with a playful contemporary twist. The movement of the skulls is further formed through the natural drying process of clay, as the clay dries out its surface expands and contracts. This slow movement, caught on film, anthropomorphises the medium imbuing the image with a sentiment of the other worldly.

Within each of the works that contribute to the Cheriton Lights Festival Rowe plays with both traditional folklore and notions of borderlands; borders between the rural and the urban, the traditional and contemporary, the mythic and the real. Displayed or projected in different spaces throughout Cheriton the works further cross borders between the domestic and the public, utilising individual’s homes for public window displays. This merging of both public and private echoes wider rural traditions where communities were bound together by celebratory rituals, each household playing a vital role in assuring an entire community’s future success.

The harvest is one example of such an event, the spirit of the corn protected and housed in domestic environments. With his series of works Rowe attempts to connect Cheriton to its rural past, linking the town and its current festival to a history of vernacular celebrations.

Text

by Laura Mansfield