Side Quests Contextual research

Research and project Development

Inspiration and reflection on provincial regional customs, intangible Heratage and hauntolgical virtual environments.

I’ve always admired Staffordshire Flatback figurines. From the misinterpreted depictions of exotic beasts—shaped by Stoke pottery workers who often lacked social mobility and formal education—to the reworked pottery castings, brightly painted in loose, garish brushstrokes to reflect the latest mass-cultural craze of the 19th century, they have a raw energy that fascinates me.

Often used as funfair prizes and affordable mantelpiece decorations, they weren’t just souvenirs but part of a mass market that captured celebrity and folk trends of the time—not as a sentimental nod to the past, but as a living, evolving form of carnivalesque culture. Here, crudity and morality blur into strange, abstracted figures and stories, full of cultural resonance but often dismissed or excluded by the cultural gatekeepers of the time, whose ideals—much like those depicted in Kipps by H.G. Wells—were shaped by rigid class distinctions and anxieties about taste and respectability.

Similarity’s can be seen in 19century provincial paintings of square cows, where abstraction met agricultural ideals, and in Staffordshire’s misinterpreted depictions of exotic animals, drawn from secondhand sources.

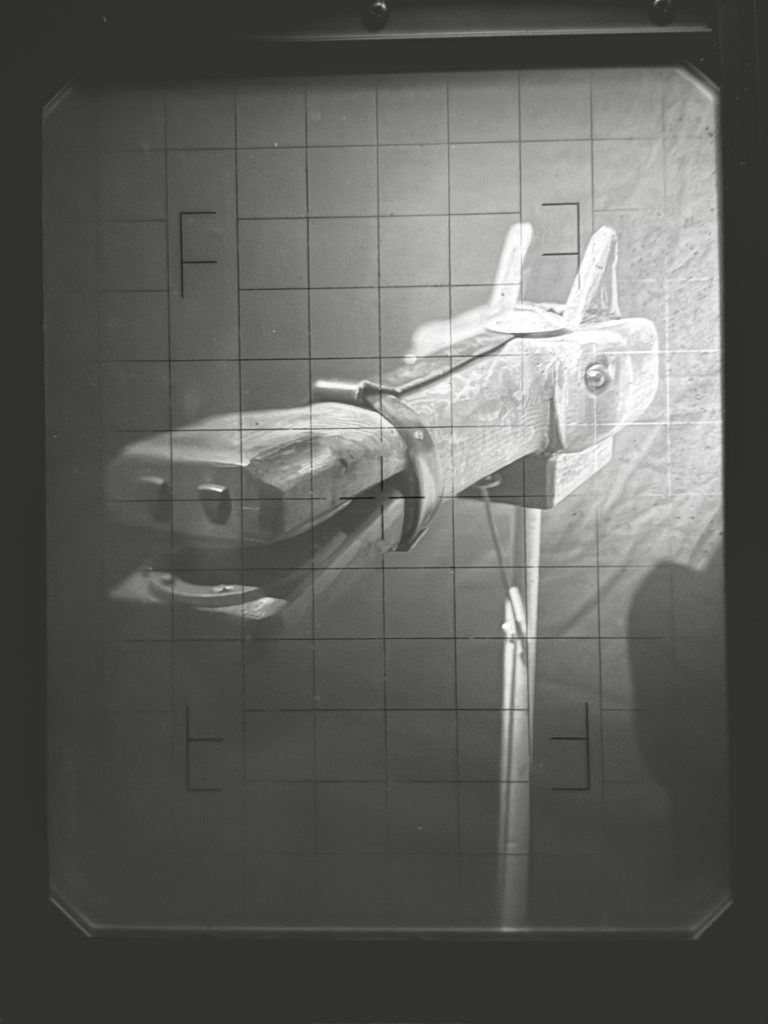

These objects and depictions weren’t constrained by anatomical accuracy they often favoured recognisability and exaduated aesthetics. A lion resembling a spaniel, a giraffe with a short neck, an elephant with hooves—these were reinterpretations shaped by print culture, oral descriptions, and theatre. The same approach carried into folk traditions like the Hooden Horse and Hobby Horse, where rural communities reworked myths and customs into something playful and ever-changing. Often crafted from materials that were on hand.

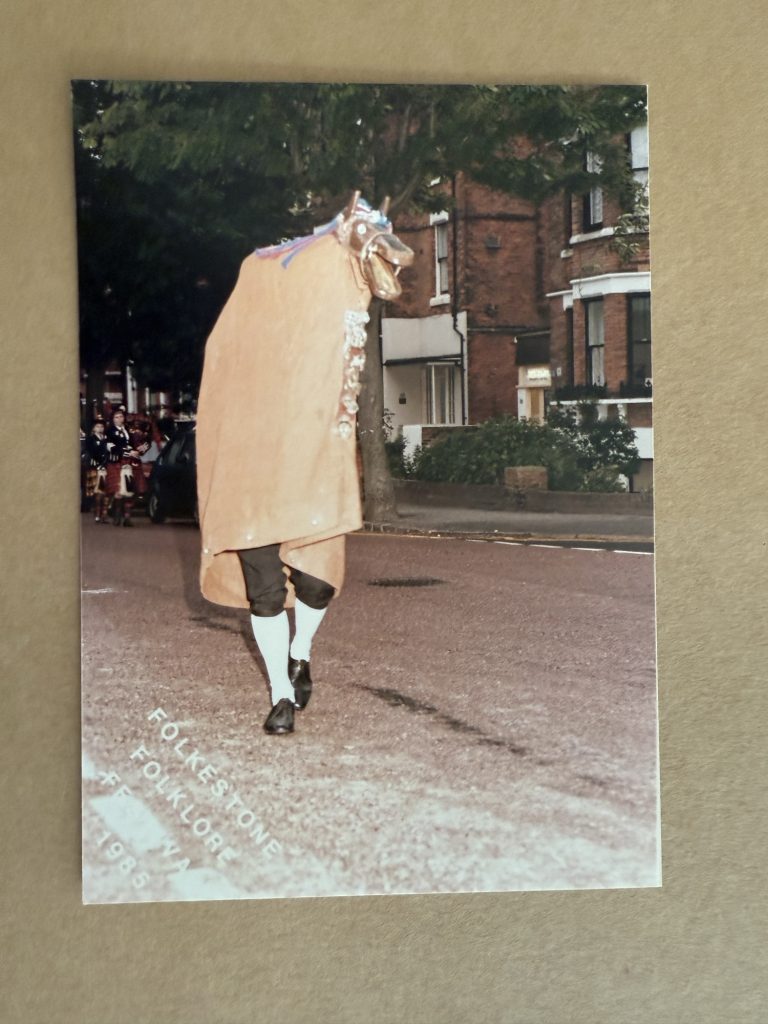

The Hooden Horse, seen in Kent’s midwinter traditions, and the Hobby Horses of Padstow and Minehead, blurred the lines between human and animal, folklore and entertainment. Like Staffordshire figurines, they existed outside elite artistic traditions, evolving through popular culture rather than formal institutions. These weren’t sentimental relics but everyday expressions of provincial creativity, shaping a visual world beyond the influence of cultural gatekeepers

the and Paintings of square cows abstract beasts. 19century custom live stock. The XR2 cow and Cosworth sheep of provincial England.

A big thanks to Coralie at Folkestone Museum for providing access to the museum archives and insights in to the origins of the Folkestone Folk Festival. Particularly intriguing were the discussion’s surrounding the social and political context that were attempting to leveraging Folk identity as a catalyst to promote post war European Intergration. Folkestone desire to assert itself as internationally recognised destination for these types international activities.

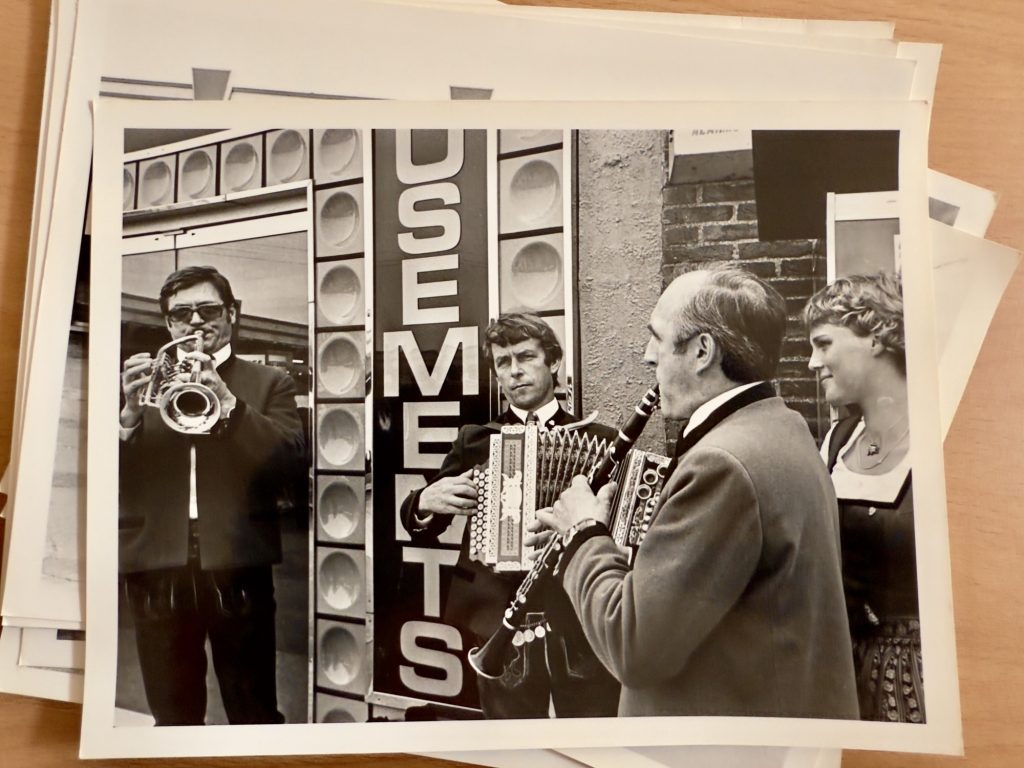

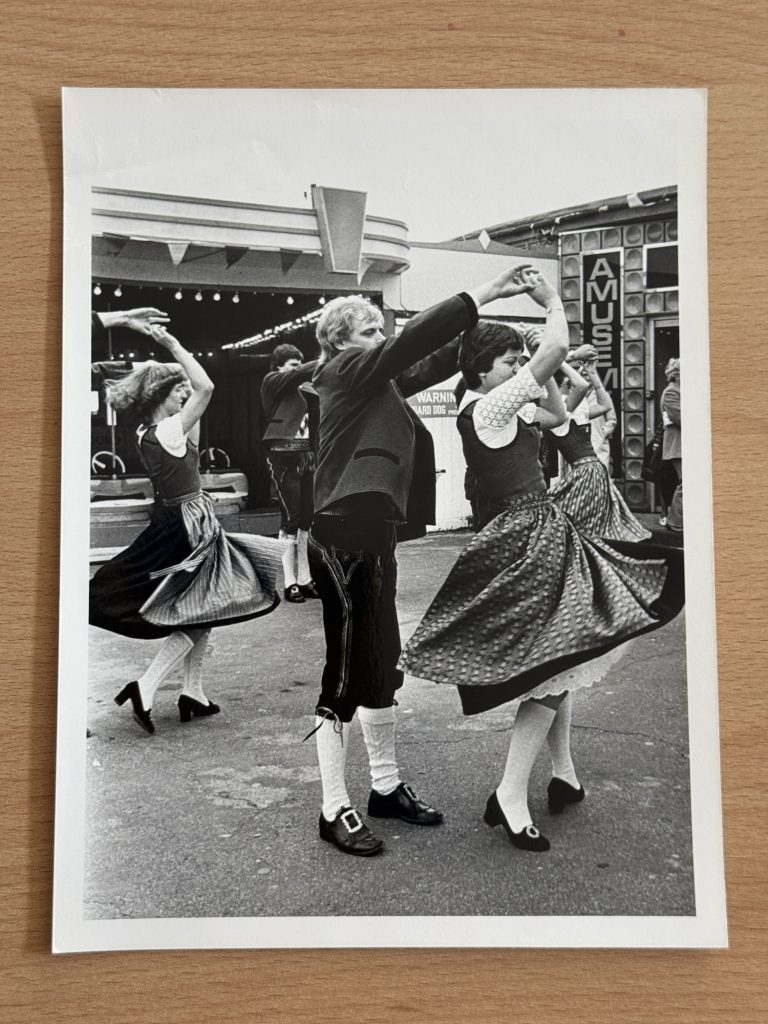

The Folkestone Folk festival documentation is extensive and depicts a series of structured events and performances at key venues and locations around the town including the leas bandstand, the rotunda amusements site as well as the town centre.

The images show little evidence of the anarchic carnivalesque origins of European folk culture. With many of the folk groups appearing to perform a form of what I would describe as civic pageantry.

My interest in the Folk Archive has been the starting point for this project, sparking a desire to explore how local traditions and material culture can be documented, interpreted, and brought into creative practice. Through this curiosity, I began forging links with SD Projects, the multidisciplinary Folkestone-based studio, and with King’s College London’s AI Lab, whose expertise in artificial intelligence and large language models offered new possibilities for storytelling.

These connections have gradually shaped the project into a collaborative exploration of the archive as a shared community resource. Working with SD Projects provides a framework for hands-on, design-led experimentation, while the AI Lab allows us to investigate how archival material can feed into quest-based narrative and interactive storytelling frameworks. My own photographic and craft-based skills, alongside my experience in teaching virtual environments, have enabled me to act as a bridge between these spaces—supporting students’ explorations of ludology and game-based design while also experimenting with Unreal Engine prototypes and interactive narrative forms. In this way, the project has evolved organically from personal research interests into a collaborative, interdisciplinary process that tests new ways of engaging with both archive and audience.