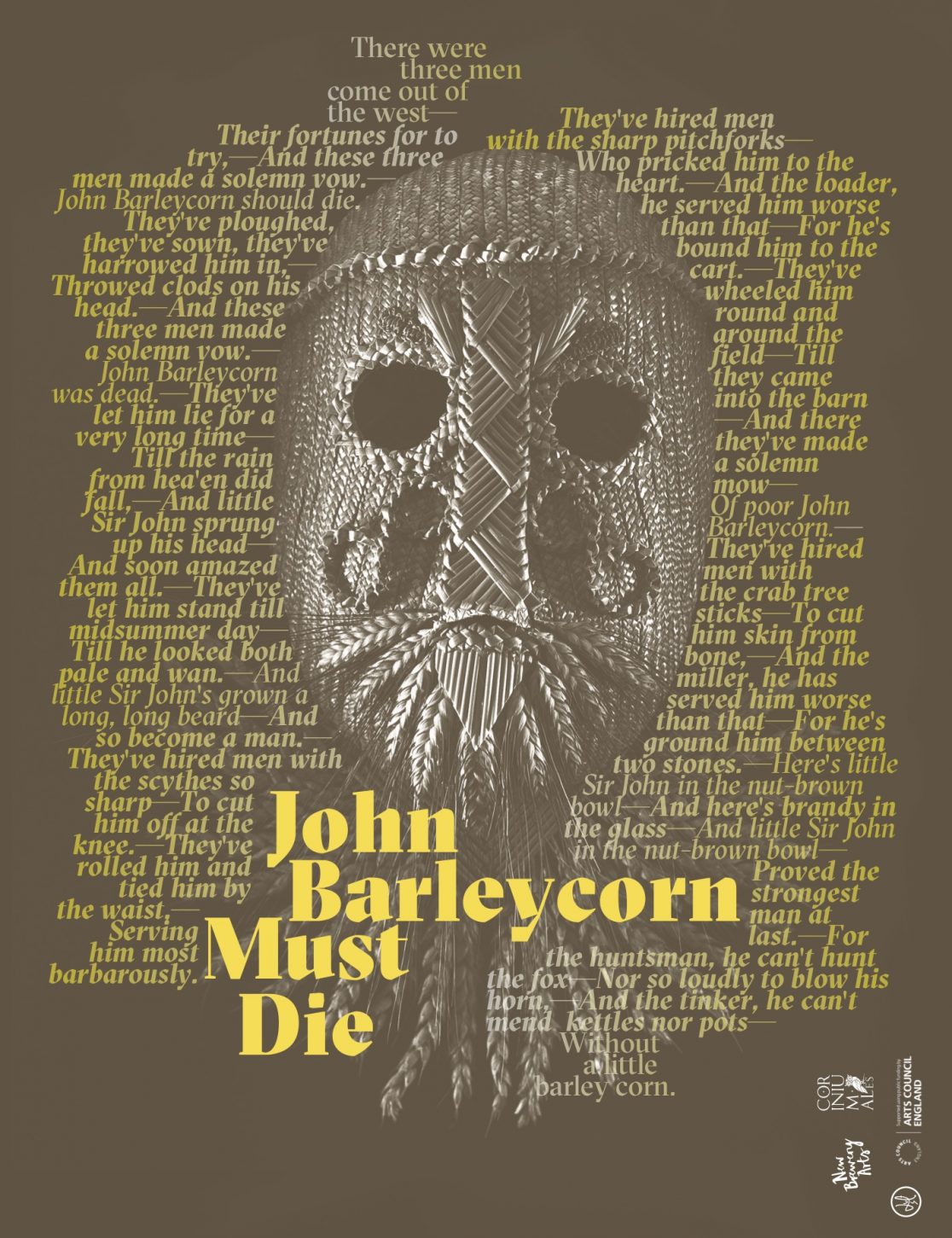

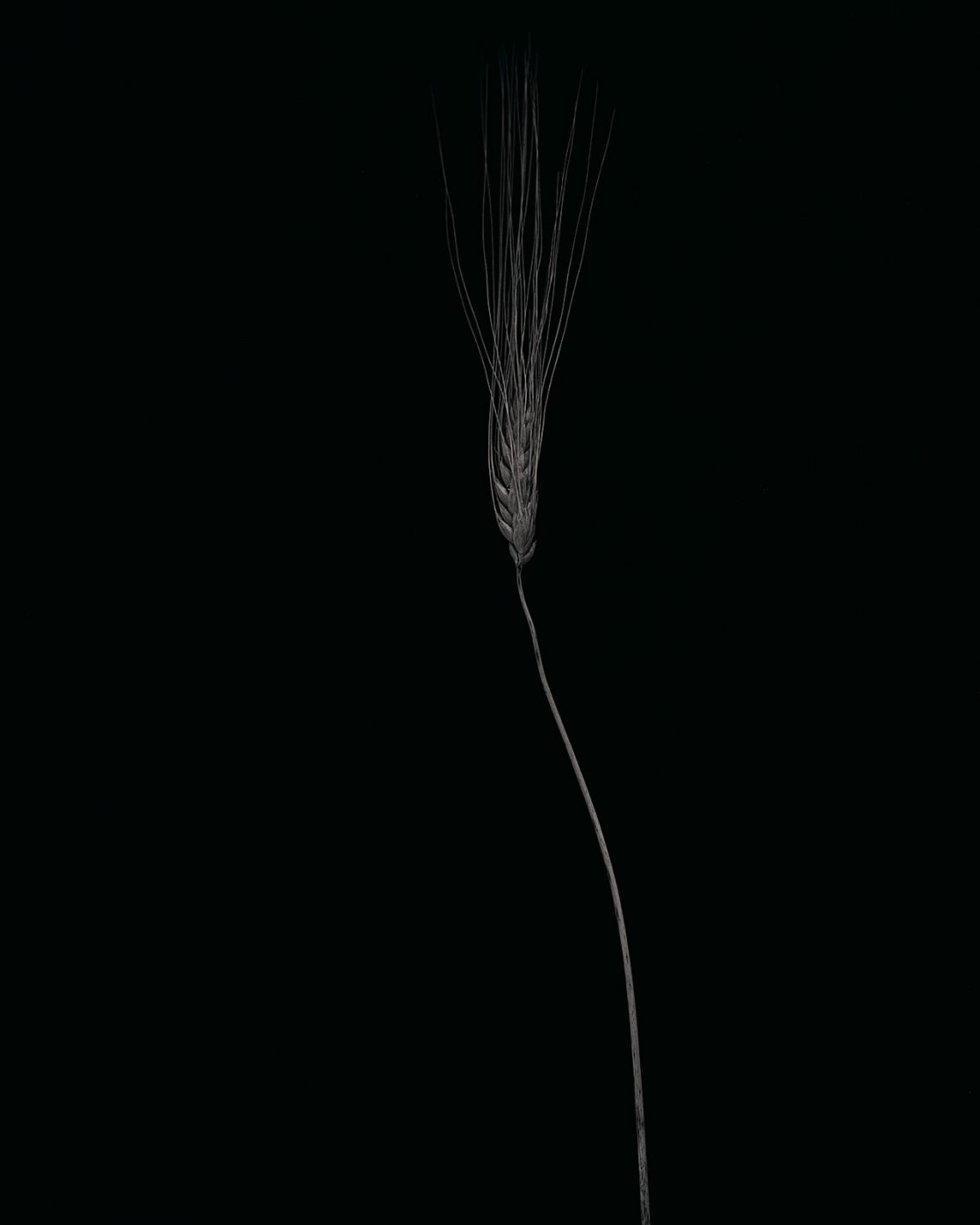

John Barleycorn Must Die

The personification of barley

Services

- Photography

- Curatorial

- Art Direction

- Sculpture

- Film

- Game Development

Sat 15thJune-Sun 25 Aug 2019

open Mon-Sat 9am-5pm,Sun 10am-4pm

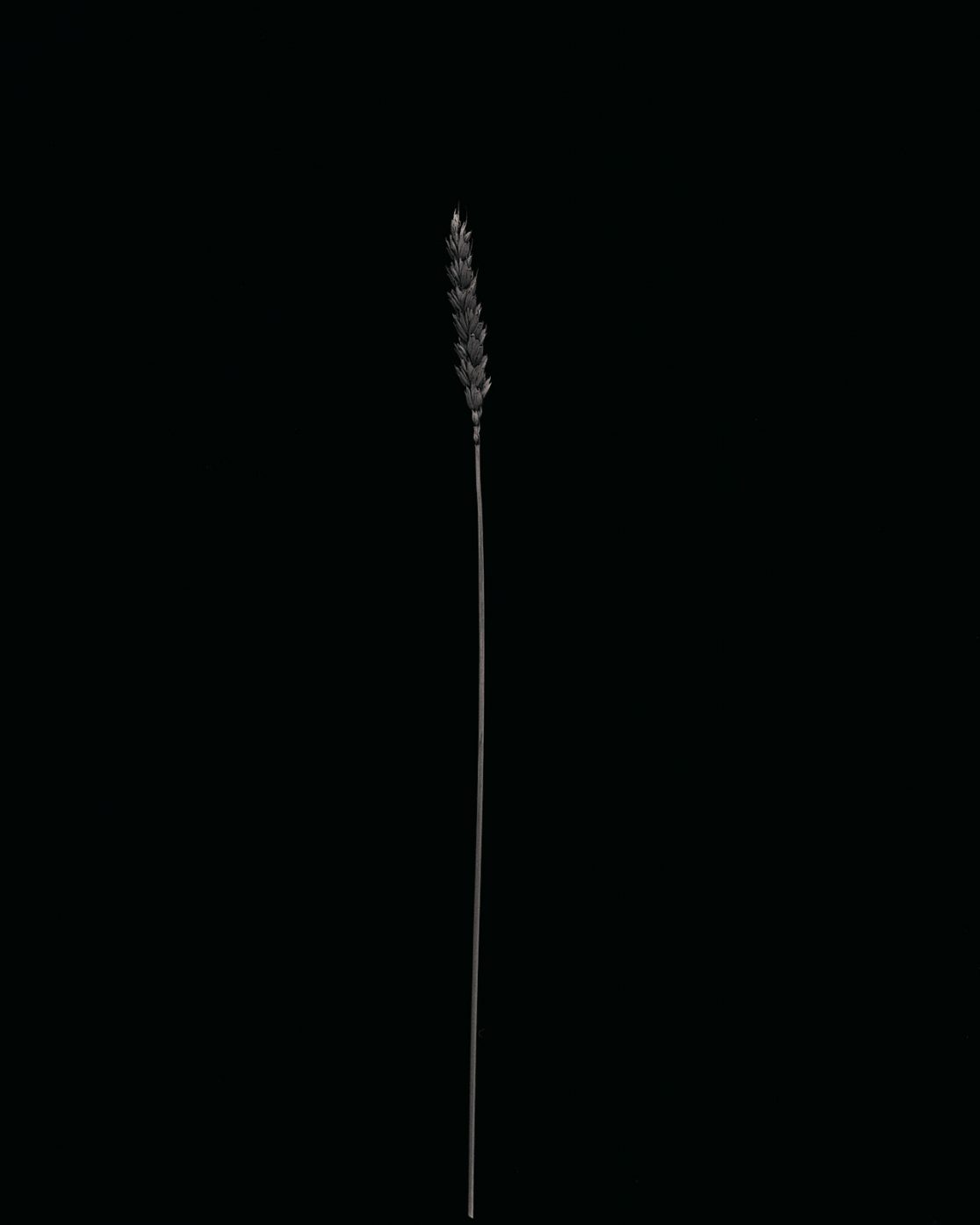

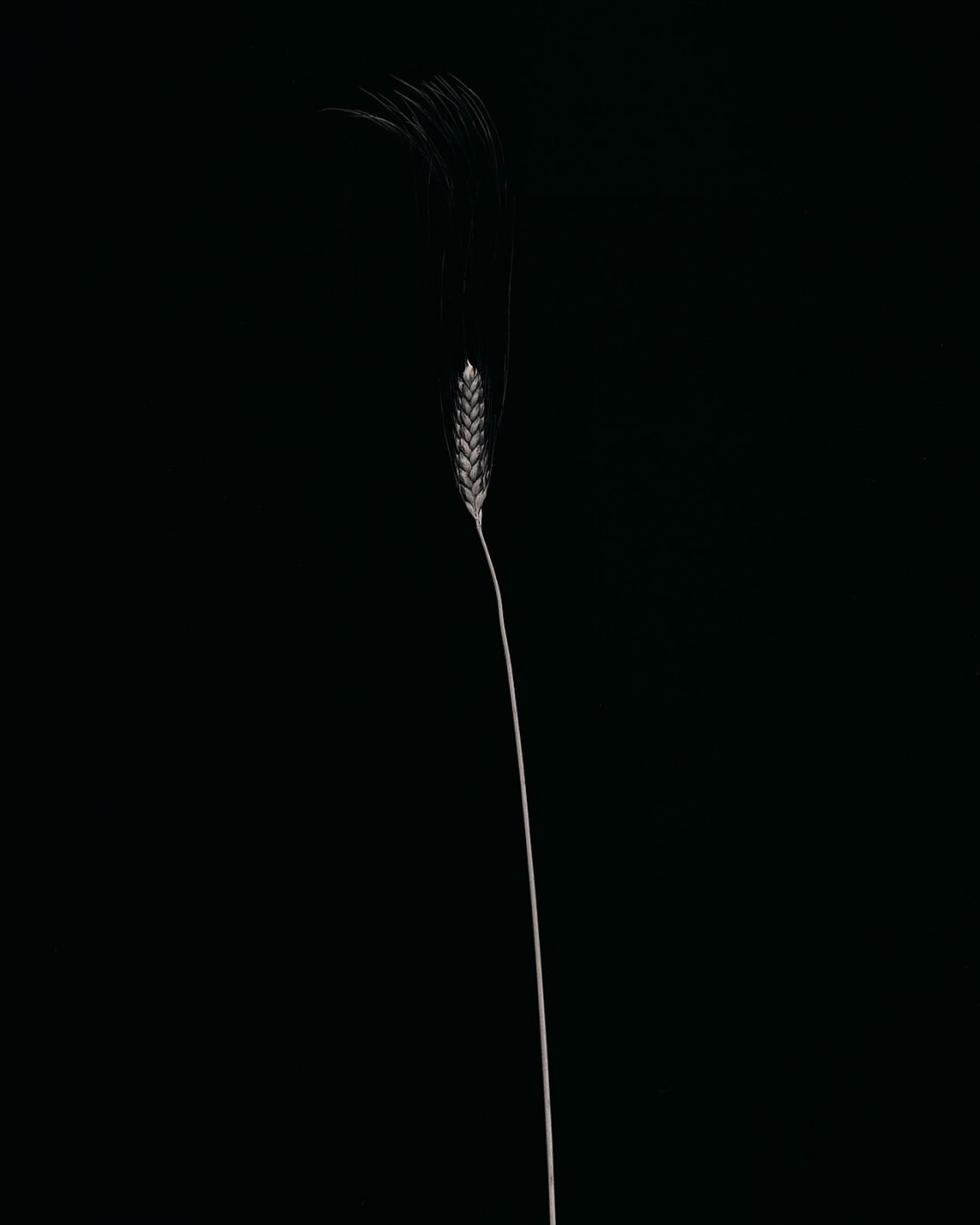

The exhibition brings together a collection of work by artist Matt Rowe and accompanying research materials gathered in collaboration with curator Laura Mansfield. The artefacts and artworks reflect upon the story and tradition of John Barleycorn. Appearing in a 17thCentury English folk song of the same name, John Barleycorn is the personification of barley and its associated food and drink. The lyrics detail the lifecycle of barley from grain to harvest to bread and beer and the seemingly indestructible spirit of the crop. Meeting, socialising and working with individuals in the locality of New Brewery Arts Matt has developed a number of collaborative works which re-consider the John Barleycorn myth and its resonance within contemporary Cirencester.

- Local hurdy-gurdy player Mike Smith has recorded a version of John Barleycorn Must Die which will be played live during the opening & appear as a soundtrack to throughout the exhibition’s duration.

- Cirencester based craft brewers Corinium Ales have produced a new brew using Chevallier malt, a heritage variety of barley that is seeing a contemporary revival in the brewing industry.

- Open source mapping data on agricultural land surrounding Cirencester has been used in a Virtual Reality gaming environment where players can search for the spirit of John Barleycorn.

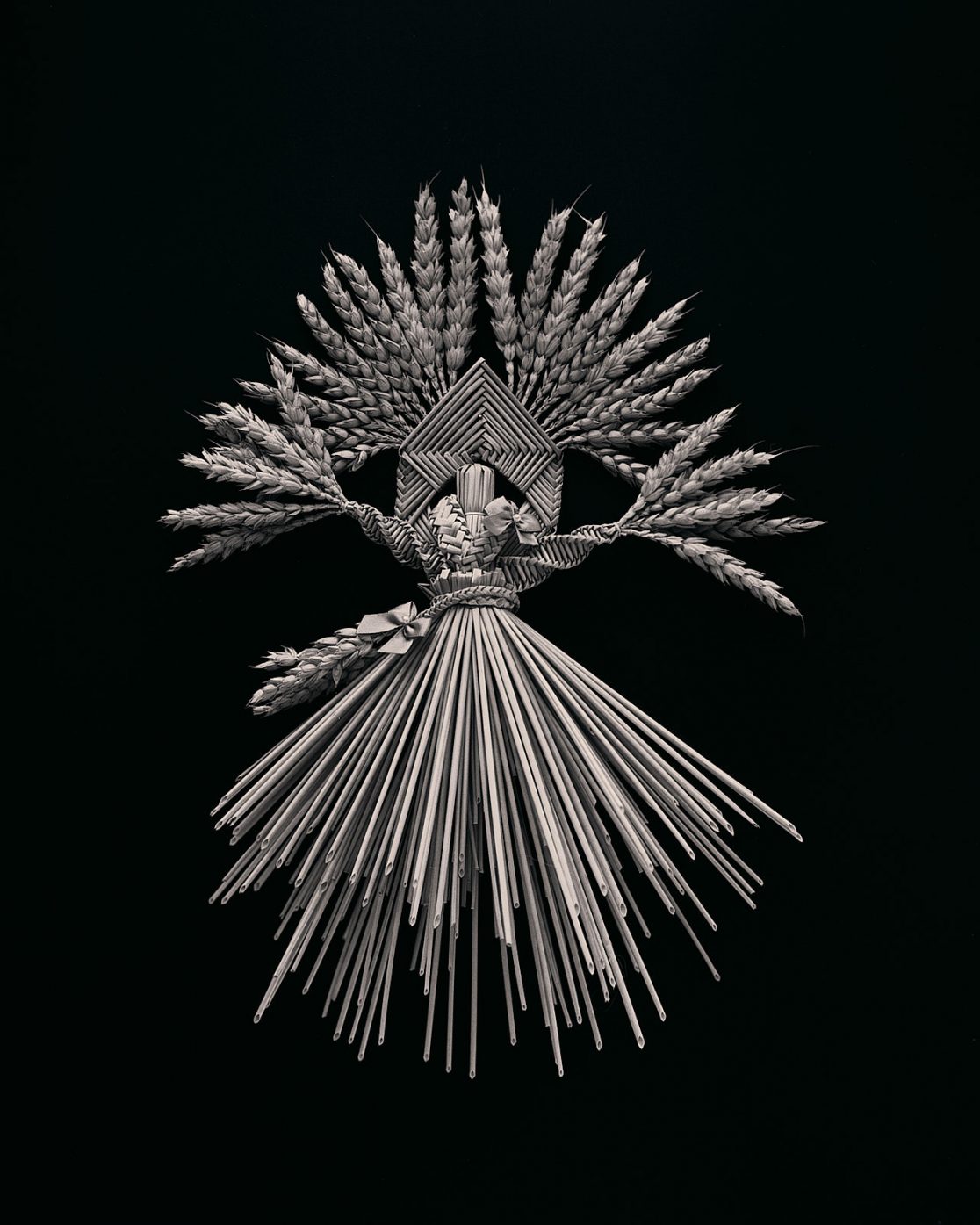

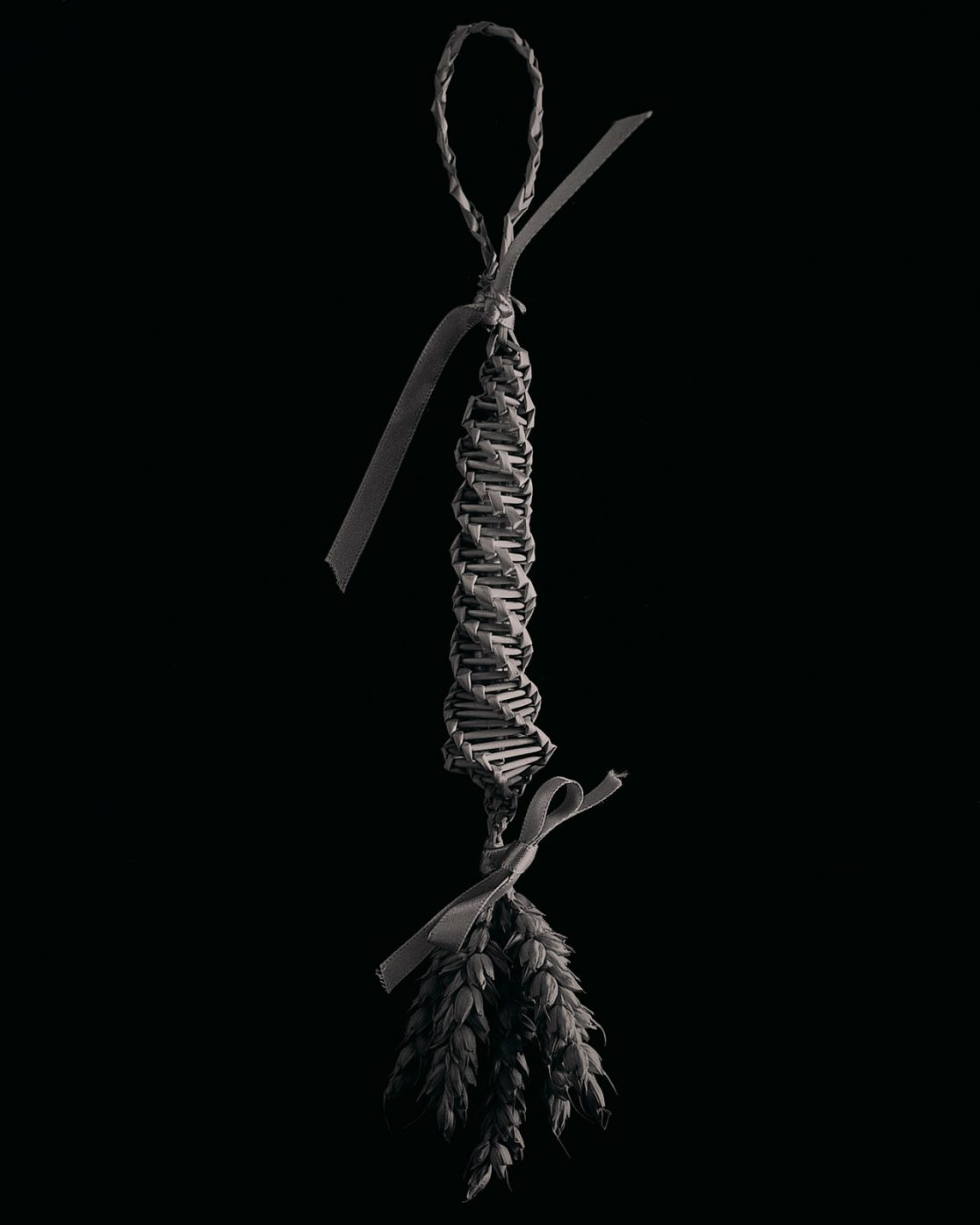

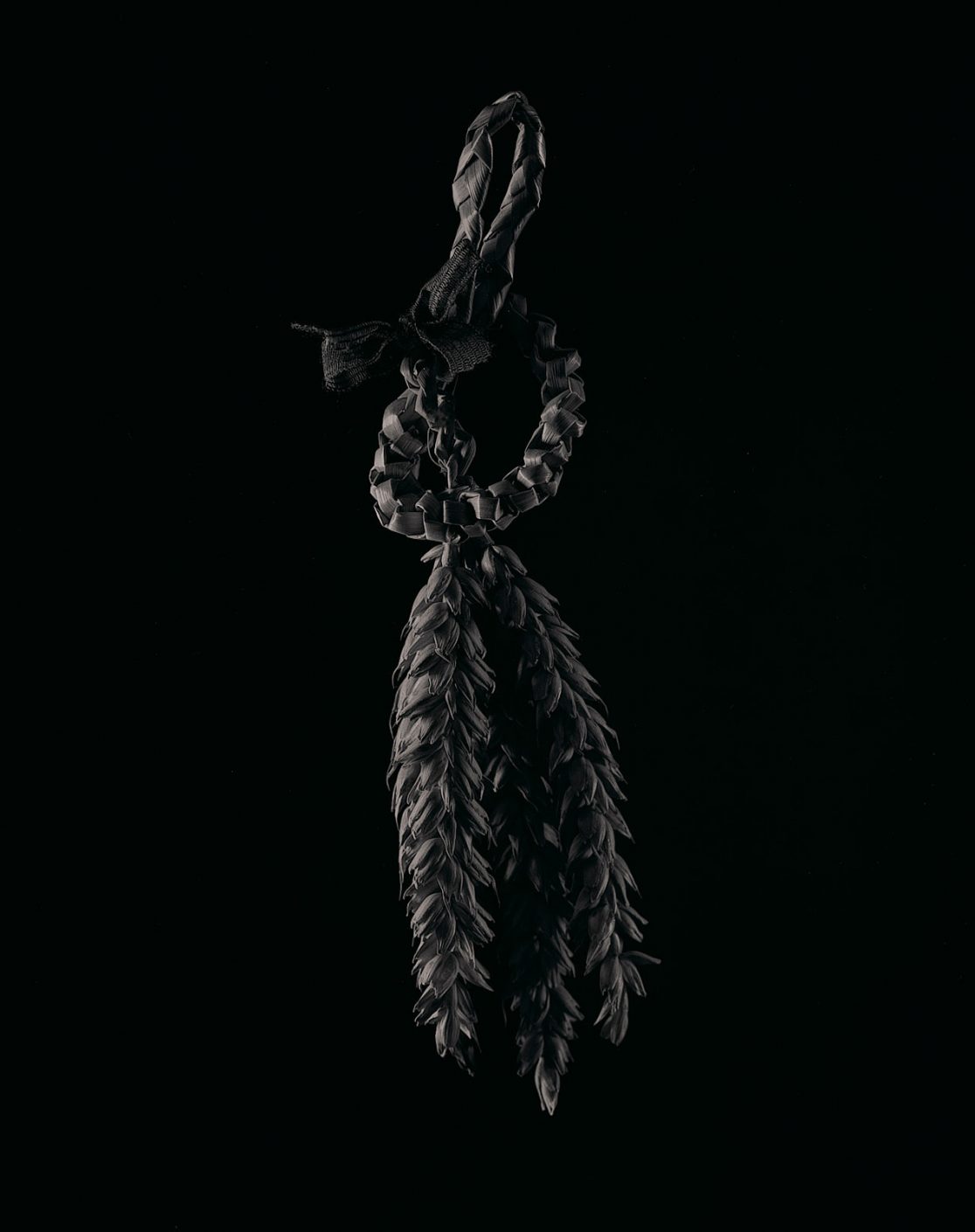

- Richard Baddily, Carol Partridge & Anthony Gay Members of The Guild of Straw Craftsmen, & Somerset based maker Audrey Rolfe have loaned examples of traditional corn dollies for display within the exhibition

A history of John Barleycorn

The story of John Barleycorn is one of agricultural tradition. Appearing in a 17thCentury English folk song of the samename, John Barleycorn is the personificationof barley and its associated food and drink. Wherever cereal crops were grown similar myths and stories of origin can be found. The following text attempts to trace the history of John Barleycorn, from his evolution in the dung piles of Neolithic man to contemporary craft ales.

The midden

Modern cereal crops have evolved from wild grasses that colonised the fertile soil of Neolithic middens. The midden, meaning a dunghill or pile of refuse is a word of Scandinavian origin derived from the Danish modding from mog, muck and dynge, pile. The midden was where Neolithic men / women deposited their waste. As hunter gatherers, wild grains would be an important part of their diets. Ingesting wild grains, seeds would consequently be deposited on the middenand quickly flourish in its nutrient richsoil. Wild seeds are covered in a protective tight skin that is derived from the glumes surrounding the seed itself. Such seeds are described as hulled and the graindifficult to release or digest compared withthe un-hulled and free threshing larger cereal crops that are easily separated into protein and carbohydrate rich grain. The nutrient rich quality of Barley was well known to later cultures, for example, Roman gladiators were known as hordearii(barley men) because it formed part of their training diet. Neolithic communities would have naturally been drawn to larger seeded grains. Similarly, un-hulled types of seed would have been preferred and consequently would have gradually become more prominent in the expelled waste of the dung heap. As they colonisedthe midden, these different wild grasseswould cross-fertilise — windblown pollen creating hybrid varieties which formed the ancestors of contemporary cereal crops. From archaeological discoveries and research into the common genes found indifferent generations of plants it is possibleto identify wheat and barley’s family tree. The evolution of modern barley, Hordeum vulgare can be traced from wild grassesthat would have flourished on Neolithicmiddens. The oldest cultivated forms of the nearest wild relative, Hordeum spontaneumhave been found in the middle-east, dating to 10,000BC. These early varieties of barley had two rows of seed. The six- rowed form often found in cultivated varieties may have been introduced from another wild relative, Hordeum agriocrithonthat is more commonly found further East towards Tibet. Mixing the gene- pools of the wild relatives and the selectionof plants that flourished on the local middenled to the development of modern barley — plants with six rows of unhulled seed that were easier to digest and produced a greater harvest. Hordeum vulgare along withEmmer wheat became the first cereal cropto be purposely cultivated and with large scale cultivation came agricultural rituals, traditions and myths of origin.

Cultivating the land

Working in the 1930s, the Russian pioneer of modern plant breeding Nikolai Vavilovidentified different centers of origin ofcultivated plants, tracing the evolution of crops and agriculture to around 20,000BCin warm temperate climates in an area known as the Fertile Crescent centered on modern day Syria and Iraq. Throughout the Fertile Crescent there is archaeological evidence from around 10,000BCE of flint-bladed sickles for harvesting cereal grains, woven baskets for carrying them, stone hearths for drying them, underground pits for storing them, and grindstones for processing them. Today barley is the world’s fourth largest cereal crop with between 130 and 150 million tonnes of grain harvested annually. Grown in more than 100 countries the majority of barley harvested is used as animal feed, with around 20% of the annual production going to the commercial brewing industry.

Wheat gradually took over from barley as a major food cereal due to the increased numbers of grains per ear and its subsequently larger yeld. Yet, with the rise of climate change barley can be seen to celebrate a European renaissance, meeting the increasing requirements for crops that are adaptable to the shifting environmental conditions. Barley is currently cultivated over a wide range of environments from spring sowing in extreme altitudes to autumn sowing in sub-tropical regions.This diversity of environments reflectsbarley’s robustness as it is recognized as being more drought and salt tolerant than wheat and as such provides an important model for future varieties of climate tolerant crops. The International Barley Hub, a research centre at the University of Dundee has recently been founded with the aim of sharing research into barley and innovative approaches to its economic,social and environmental benefits. As wellas looking for future varieties of the crop researchers are also returning to heritage strands of barley to provide increasingly important disease and drought resistance.

Coincidentally, heritage varieties of cereal crop are also the prime material for contemporary strawcraft, most commonly Maris Widgeon wheat — a hollow, pale golden (almost white) straw with a long stem suited to weaving.

The ritual of harvest

The greatest body of agricultural folklore is connected to the harvesting of grain, whether it be wheat, barley, oats or rye. In Asia, the tears of the God Indra created the fertile Punjab basin, with his spirit residing in the crops that grew from the soil. Some of the other, more well-known corn spirits or gods were Ceres, the Roman goddess of the harvest (from which we get our word cereal); Demeter (Earth Mother), the Greek goddess of the harvest, and Isis, the Egyptian Goddess of Fertility. Others include the Cherokee goddess Selu; Yellow Woman and Chicomecoatl, the goddess of maize who was worshiped by the Aztecs of Mexico. The Maya believed that humans had been fashioned out of corn, and based their calendar on the plantingof the cornfield.

Focusing upon European traditions of harvest, John Barleycorn (the spirit of the corn) has his roots in themythical Anglo Saxon figure of Beowa(meaning barley). As the song lyrics describe,living within the ripening fields of barleyhis spirit retreats before the oncoming reapers at harvest time, taking refuge in the last of the standing crop. Throughout

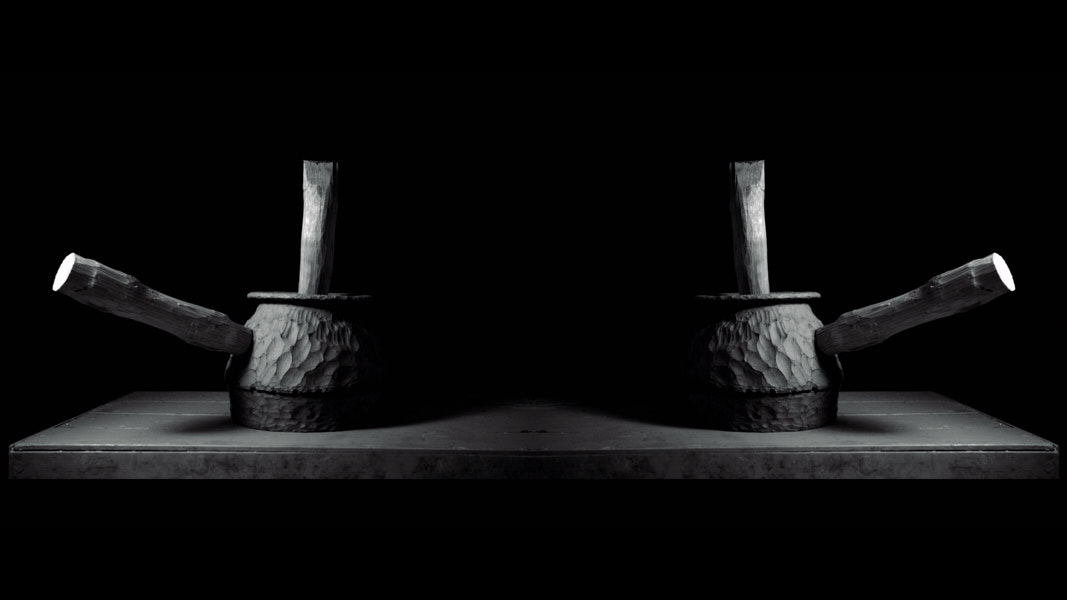

northern Europe saving this last sheaf of harvest was a common tradition, keeping the spirit safe within the remaining stalks. Fashioned into a Harvest Trophy or CornDolly, the crafted figurine functioned asa vessel to house the Spirit, letting it rest throughout the cold winter months.

Examples of early Corn Dollies were collected in abundance by the German folklorist Wilhelm Mannhardt. Later James George Frazer’s The Golden Bough: A study in comparative religion(1890) detailed examples of agricultural

rituals that occurred around the last sheaf of the harvest.

“In the neighbourhood of Danzig the person who cuts the last ears of corn makes them into a doll, which is called the Corn-mother or the Old Woman and is brought home on the last wagon. In some parts of Holstein the last sheaf is dressed in women’s clothes and called the Corn- mother… In the district of Bruck in Styria the last sheaf, called the Corn-mother, is made up into the shape of a woman by the oldest married woman in the village… Thefinest ears are plucked out of it and made into a wreath, which, twined with flowers,is carried on her head by the prettiest girl of the village to the farmer or squire… In other villages of the same district the Corn- mother, at the close of harvest, is carried by two lads at the top of a pole. They march behind the girl who wears the wreath to the squire’s house, and while he receives the wreath and hangs it up in the hall, the Corn-mother is placed on the top of a pile of wood, where she is the centre of the harvest supper and dance.”

Honoured in the harvest celebrations, the Corn Dolly housing the incumbent spirit of corn was returned tothe field, ploughed back into the earth withthe new agricultural calendar. Traditional rituals around the return to work after

the winter months often take the form ofPlough Monday. The first Monday afterepiphany, Plough Monday marks the start of the English Agricultural year. The tradition is honoured in Cirencester with a Plough Monday service held annually in the church. The Dean of the Royal Agricultural College, fellow farmers and townsfolk congregate around a traditional plough decorated with seasonal greenery that is blessed by the minister.

Sheltering John Barleycorn through the dark winter months and returning him to the soil with the start of the agricultural year was perceived to ensure a bountiful harvest. Returned to the land John Barleycorn would live again. Yet throughout the sleepy winter his Spirit does not entirely disappear, John Barleycorn does not die, his essence can be found in the grain that was harvested — he risesin the flour used for bread and bubblesup in the fermented malt of ale.

Fermenting the grain

Drinking ale made from the fermented grains of the gathered crop, the harvesters consume something of the essence of John Barleycorn — his spirit creepsfrom the fields into the ritual drinkingof the labourers. The interconnection ofharvest and drinking reflects somethingof the larger story of the evolution of modern agriculture and its produce. As the cultivation of crops developed so did the methods and means of storing and using the harvested grain. Ever since humans stopped being nomad hunter gatherers and settled in one location, cultivating thegrasses that flourished on the midden, theyhave been fermenting the grains to make bread and beer. The poet John Ciardi famously commented “fermentation and civilisation are inseparable”. Grain soaked in water, so that it starts to sprout, tastes sweet. Moistened grain produces diastase enzymes, which convert starch within the grain into maltose sugar, or malt. This process occurs in all cereal grains, but barley produces the most diastase enzymes and therefore the most maltose sugar. At a time when few other sources of sugar were available, the sweetness of this “malted” grain would have been highly valued, prompting the development of deliberate malting techniques. If the malt is left longer, or heated, other starch-converting enzymes, which become active at higher temperatures, turn more of the starch into sugar, meaning more sugar for the yeast to transform into alcohol creating a simple beer. The ancient Egyptians believed that beer was accidentally discovered by Osiris, the god of agriculture and king of the afterlife. The myth tells how Osiris prepared a mixture of water and sprouted grain for a sweet drink, but forgot about it and left it in the sun. Returning to his malt later, he found that the mixture had fermented. Deciding to drink the fermenting mixture he was so pleased with how it tastedand the effect it had on his body that hepassed his knowledge on to humankind. Beer then, was a magical drink. The spiritof John Barleycorn effervescing in the beerof the agricultural labourers introduces a mysticism to English harvest traditions.

The communal cup

Long before pottery was available, malted drinks would have been brewed in pitch- lined baskets, leather bags or animal stomachs, hollowed-out trees, large shells, or stone vessels. Sahti, a traditional beer made in Finland, is still brewed in hollowed-out trees. Depictions of beer from 3000BCE in Sumeria, an area now known as southern Iraq, generally show two people drinking through straws from a shared ceramic vessel. The advent of pottery meant that individual cups could just have easily been used for drinking malts. However, the ritual of sharing the fermented drink took priority. Drinking alcohol therefore, has been an activity in which social or communal interaction has always been deemed necessary.

Drinking from a shared cup instills communal friendship and alliances. The Anglo-Saxon tradition of waissailing is centred upon drinking from a shared vessel to mark the start of new year celebrations. At the beginning of each year, the lord of the manor would greet the assembled multitude with the toastwaes hael, meaning “be well” or “be in good health”, to which his followers would reply drink hael, or “drink well”. A large bowl would then be passed from one person to the next, each taking a sip of the warmed ale, cider or wine. The ritual would inevitably turn into a more carnivalesqueaffair as the effects of thedrink were felt. Akin to harvest drinking traditions the spirit of the fermented grain would take hold, and a wild revelry ensue. Once Christianity became the dominant religion in Europe the risk of over indulgence in alcohol was warned by the Church. In Cirencester, a character of thebuffoon or fool can be seen carved into the door of the church. The buffoon was a figure that provided amusement throughinappropriate appearance or behavior, indicating the ridicule that can come withexcessive consumption of ale.

Resurrecting John Barleycorn

It is fitting that New Brewery Arts hostsan exhibition exploring the spirit of John Barleycorn. Not only was Cirencester the second largest Roman town (Corinium) to London (Londinium) — with the production of beer being an important part of Roman diet and daily life — but, in the late 1700s the New Brewery Arts building was home to Cirencester Brewery, one of the most complete breweries of its size outside London and by the late1800s the town’s largest employer. Working with local brewers Corinium Ales, the exhibition contains a new brew made with heritage malts — resurrecting the spirit of John Barleycorn in the fermenting grain of a contemporary craft beer.

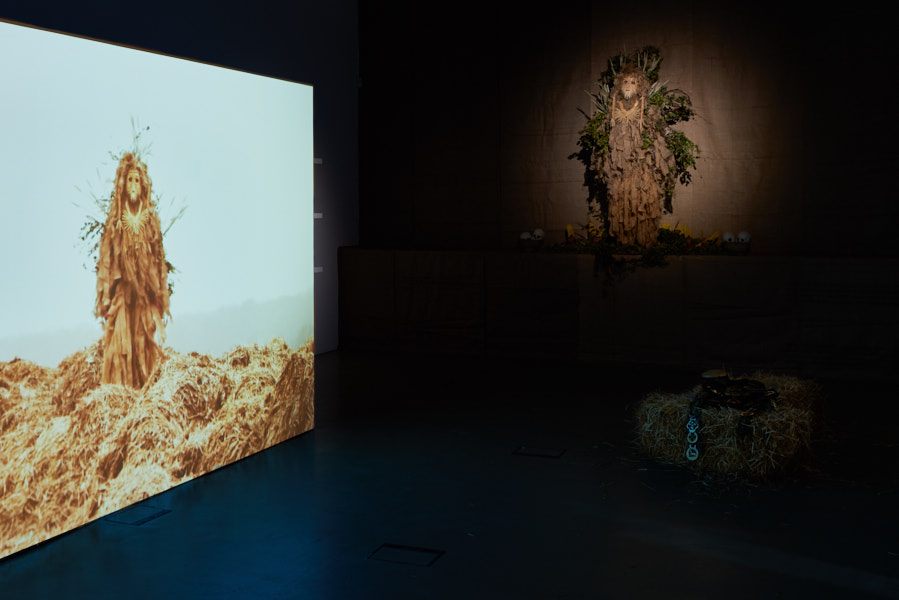

Looming over the exhibition isa costumed figure, a physical manifestation of John Barleycorn created by the artist Matt Rowe with the aide of Carol Partridge, a member of the Guild of Straw Craftsmen. The mask and adornments to the costume are woven with heritage varieties of cereal crop. In both the beer and the body of John Barleycorn heritage strands of barley make an appearance, his contemporary presence crafted from a history of agricultural methods and folk traditions. Throughout the gallery the droning notes of a hurdy- gurdy infuse the space with local musician Mike Smith’s haunting version of John Barleycorn Must Die bringing a looming uncertainty to the traditional song and the surrounding artworks reflecting something of the precarious role of John Barleycorn in the contemporary era.

Download the exhibition text and poster: Link