Folklore as Material to Fight The Culture Industry

Contrary to what one is sometimes led to believe by a cursory or superficial reading of the works of Adorno, his critique of the concept of the ‘culture industry’ does not, in his mind, equate to a condemnation of popular art. When he attempts to define it – either in the seminal essay ‘The Industrial Production of Cultural Goods’, written with Horkheimer and published in 1947 in The Dialectic of Enlightenment, or in ‘The Culture Industry’, an essay published in 1964 in the third edition of the journal Communications – he takes care in each case to draw a clear distinction between the two: the first, the ‘culture industry’, which Adorno describes as the integration of artworks (that have become ‘cultural goods’) into the general system of production and mass consumption that then determines their form and content; the second, ‘popular art’ (this is equally valid for its corollary, fine art), which relates back to an earlier state of the same conditions of production and reception. Adorno, to put it another way, takes great care in these two texts to emphasise that the distinction he makes between what he calls the culture industry and what escapes it – for which he reserves the term ‘art’ – does not replace the old distinction between fine art and popular art, or between what he still calls high and low art. Fine art, as well as popular art, is transformed, or rather is suppressed, as such by the culture industry, the former losing its seriousness, the latter its robust and resistant nature – in short, that which gave both their artistic character according to Adorno.

That said, I would now like to propose a hypothesis. If it is true that the culture industry causes popular art and fine art to lose – or rather it supresses – their artistic character, and if it is true that it appears increasingly omnipresent, in that it seems less and less possible to place oneself outside its rules, and that

it gives the impression of being a perpetual inside and a perpetual present,

it could nevertheless be argued that popular art and fine art – understood as historically designated and historically outmoded forms and content – offer the possibility all the same of constituting such an outside, and of offering

material, in the Brechtian sense, for the development today of works of an artistic character. The seriousness of the former, the robust and resistant nature of the latter, could in fact be means of introducing a rupture in the continuous flux, or puncture the overblown bubble, of the culture industry.

Let me return briefly to one significant aspect of the effects, one might say

ill effects, produced in art by the culture industry: that of standardisation. Conceived above all else to satisfy a demand, to which in reality they conspire to maintain, the goods produced by the culture industry are in fact characterised by their relative similarity to one another and by the relative poverty of their form and content. In order to facilitate their circulation (exhibition and sales) and production, it makes sense to eliminate from them anything that might make them distinct or singular.

The keen follower of the current development of what is commonly referred

to as ‘contemporary art’ will have no doubt noticed that what was originally conceived to exist outside the system, barely escapes from it today: compared to the art of the sixties or seventies, of which it claims nonetheless to be the continuation, a large part of contemporary art in reality merely consists in recycling empty forms and content for commercial ends that it accepts more or less voluntarily.

Global art – judging by its major international art fairs or main press channels – seems, under the control of the culture industry today, to have become homogenised and standardised: everything you see looks the same, and, moreover, everything that looks the same has an air of déjà-vu about it.

Everything? Fortunately, not all! For those who take a moral and political decision to look for an alternative, it is possible, indeed necessary, to put in place strategies to introduce the never-before-seen and the extraordinary – in order, that is, to reintroduce art.

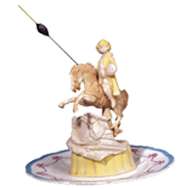

It is at the level of these strategies, therefore, that one might consider the use of fine art or popular art as material for new artworks. On the subject more specifically of popular art, this is the tactic employed by a certain number of individuals and venues, such as the B&B Project Space in Folkestone, England, and those artists invited to take part in its second edition of Vernacular Events during the summer of 2011.

Preferring the notion of folklore, in fact, to that of popular art (‘folklore’ in the widest sense of the term, meaning the combined knowledge and power of the people, including outside the art world and linked to a specific time and place), the B&B Project Space asks invited artists to reactivate what already lies – and more importantly, continues today – in the hardy and resistant nature of folklore in the county of Kent and the district of Shepway. In this way, they might hope to find in the ‘local’ something not previously seen in the

‘global’ – it won’t be the first time in history that the particular, as a powerful carrier of a concrete universality, is juxtaposed against an abstract generality. Adopting it, appropriating it as material, the invited artists create works that break away forcefully from the homogeneity discussed above. There are elements of the extraordinary and the never-before-seen in the works of Matthew Cowan, of the Ghost Collective (Sarah Sparkes and Ricardo Vidal) or of Matt Rowe! Something that we might miss at first, but that then suddenly hits us: a valuing of knowledge, an artistic value, above their commodity status.

François Coadou

Philosopher, professor at the école supérieure d’art de TPM, and art critic (member of AICA)

Translation by Jen Thatcher