Reconstructing Lost Rotunda Objects Using AI and Archival Film

Over the last couple of decades I’ve collected a huge archive of photographs from around the Rotunda and Folkestone seafront — shot on an old Hasselblad, a Rolleiflex, various 35mm bodies, and whatever else I had to hand. Many of these were taken just before demolition or major changes, so the archive has gradually become a record of things that simply don’t exist anymore.

Recently I’ve been revisiting this material with a new purpose: to extract objects from these analogue images and bring them back into my virtual production workflow as quick, usable 3D assets. I’m not talking about full photogrammetry here — this is about speed, practicality, and getting heritage elements back into a build with minimal fuss.

Digitising the Originals

Most of the negatives and slides have been scanned using a slide scanner over the years, and I’m still rescanning some to maximise detail. Medium-format film has a lovely density and grain that actually works in your favour for AI processing, as long as the scans are clean and high-res.

Once digitised, these images give me enough information to isolate objects that I want to rebuild — old fairground figures, signage, cones, props, etc.

AI-Assisted Object Isolation

This is the part of the workflow that has changed everything. Instead of spending an hour masking a subject in Photoshop, I’m now using ChatGPT’s image tools to quickly cut out objects from the scanned film. These might be rides from the Rotunda, ice-cream signage, old mascots — anything that appears cleanly in a frame.

The steps are simple:

Upload the scanned photo Ask ChatGPT to isolate the object (removing people, seafront clutter, etc.) Clean, denoise, and colour-correct the cut-out Export it as a transparent PNG or silhouette

For simple objects it’s honestly quicker than setting up a full photogrammetry session, especially when the original photos were never taken for that purpose.

Sending the Isolated Object to Meshi AI

Once the object is isolated, I drop it into Meshi AI (I’m currently just using the trial version). Meshi is surprisingly good at taking a single image and generating a usable 3D mesh with textures.

The workflow goes something like this:

Upload the transparent PNG Let Meshi generate the rough 3D form Export the mesh + texture Bring it straight into Unreal, Unity, Blender, or whatever build you’re working on

It’s not perfect — you’ll still want to tweak shapes, normals, and texture seams — but as an indie workflow, it cuts the time down massively. A small fairground figure that might take an evening to model by hand can now be roughed out in minutes.

Why This Matters for Heritage Work

A lot of the objects I’m pulling from these old photos simply don’t exist anymore. They were thrown out, scrapped, painted over, or demolished along with the wider site. Being able to rebuild them quickly from a single archival photo gives me a practical way of bringing that intangible heritage back into virtual production environments.

For me, the aim isn’t perfect reconstruction — it’s about retaining the atmosphere, the texture, the “feel” of the original spaces. This workflow gives me:

faster turnaround cleaner assets direct lineage from analogue image → 3D object a way to bring lost Folkestone structures into modern creative tools

And for indie-scale projects, this balance of speed and authenticity is ideal.

Bringing Archival Assets Into Virtual Production

Once I’ve generated a quick 3D mesh from an archival photo, it drops straight into my virtual production setup. My system runs through Unreal Engine with the Blackmagic Ultimatte 12 and a DeckLink card for live capture, which gives me a clean real-time composite to test ideas quickly. What’s useful about the AI-generated models is that they come in already textured and UV’d, so they slot neatly into my scenes without needing hours of prep work.

Working in Unreal 5.6+

Unreal 5.6 finally solved most of the stability issues with DeckLink inputs, and that’s made this whole workflow far smoother. I keep the setup simple:

Ultimatte for hardware keying DeckLink feeding directly into Unreal A single master camera in Sequencer Light-touch adjustments to the imported mesh

This gives me enough control to position objects, test lighting, and composite a performer against rebuilt Rotunda elements — often within minutes of isolating the object from the original scan.

AI for Fast Scene Building

One of the unexpected benefits of this process is how quickly I can build out a scene. Instead of modelling everything from scratch or setting up full photogrammetry (which isn’t possible with old analogue shots anyway), AI lets me extract props, signage and fairground pieces in a fraction of the time.

It’s not perfect reconstruction, but it preserves the visual language of the original environment, and that’s what matters for the kind of heritage-led projects I develop.

Why This Works for Indie Production

This approach sits nicely between speed and authenticity. As a solo or small-team developer, I don’t need forensic detail — I need assets that feel right, load quickly, and let me iterate. By combining my analogue archive with AI isolation and Unreal’s VP tools, I can rebuild lost spaces in a way that’s fast, practical and rooted in the original material.

It’s also a way of keeping the Rotunda alive. These old slides and negatives now feed directly into modern creative tools, letting me reintroduce vanished landmarks into new XR, VP and game environments.

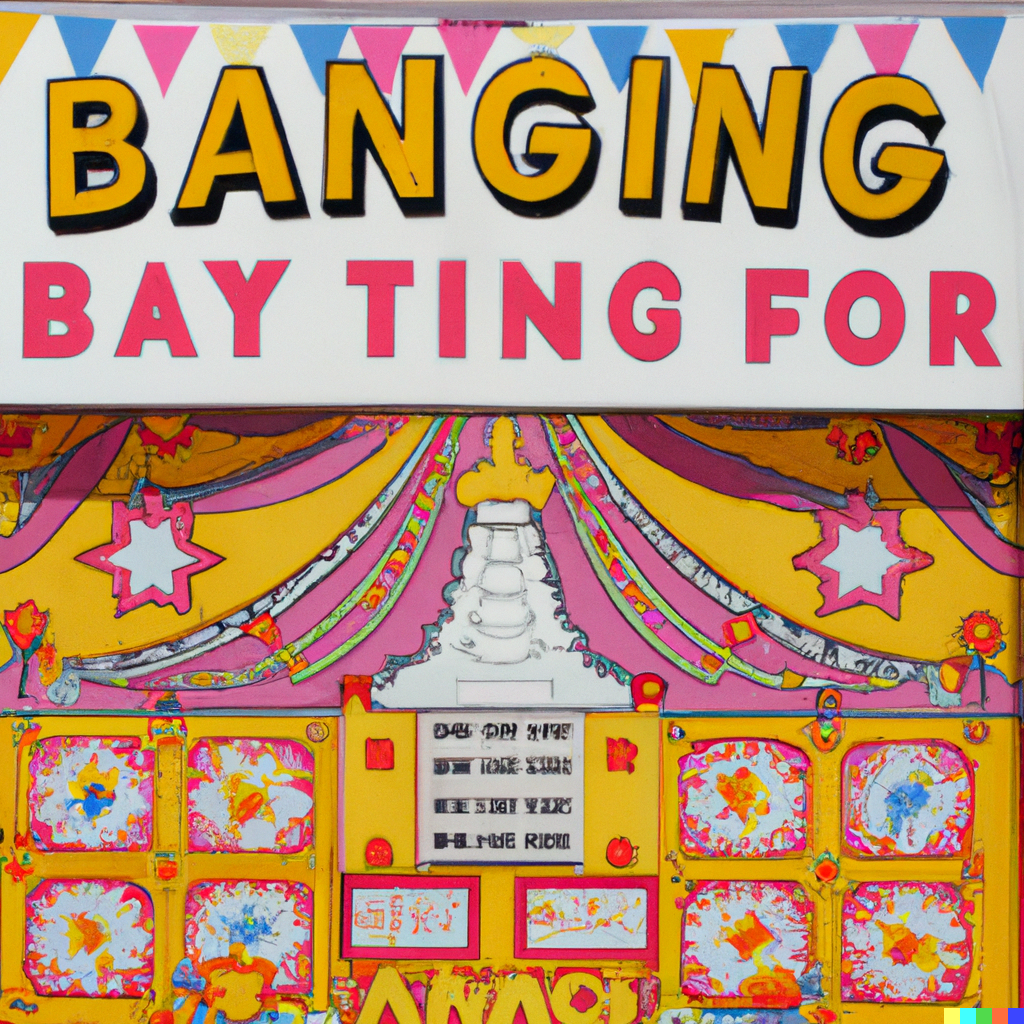

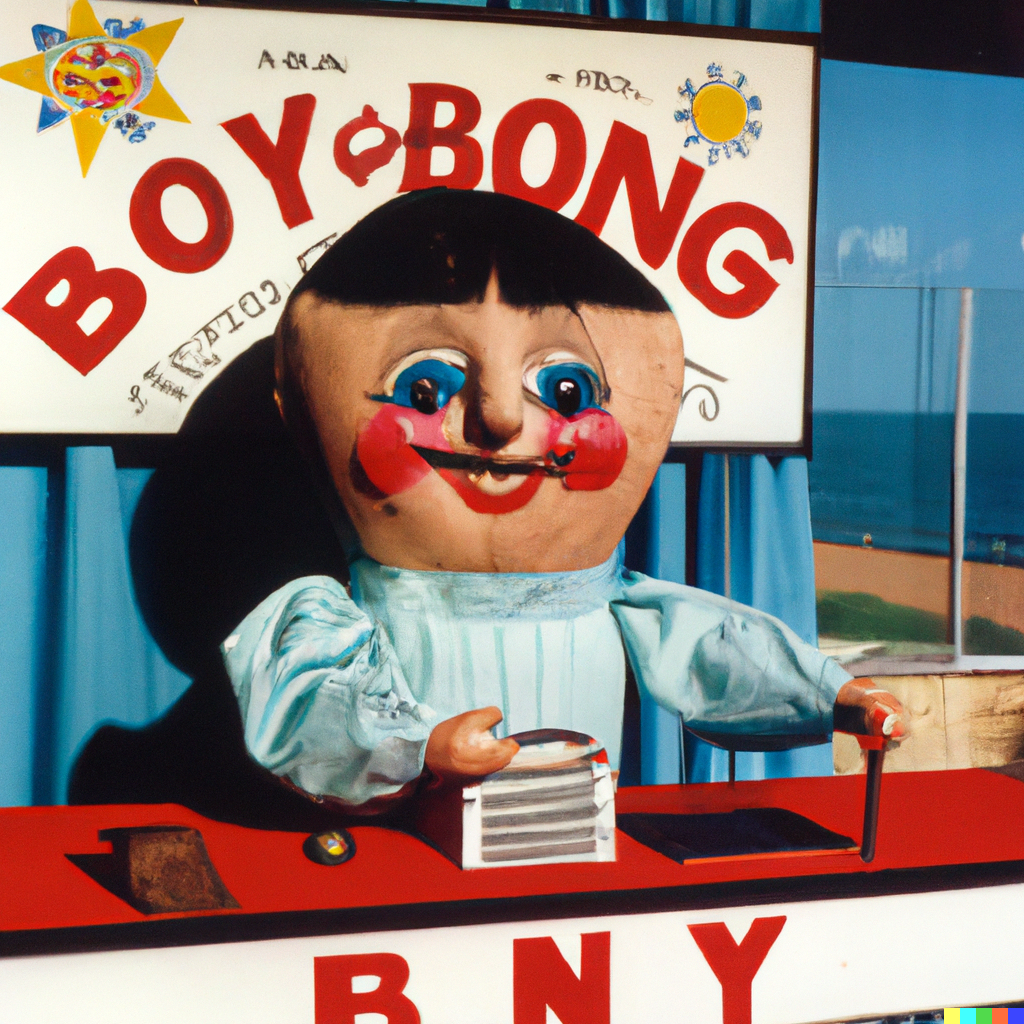

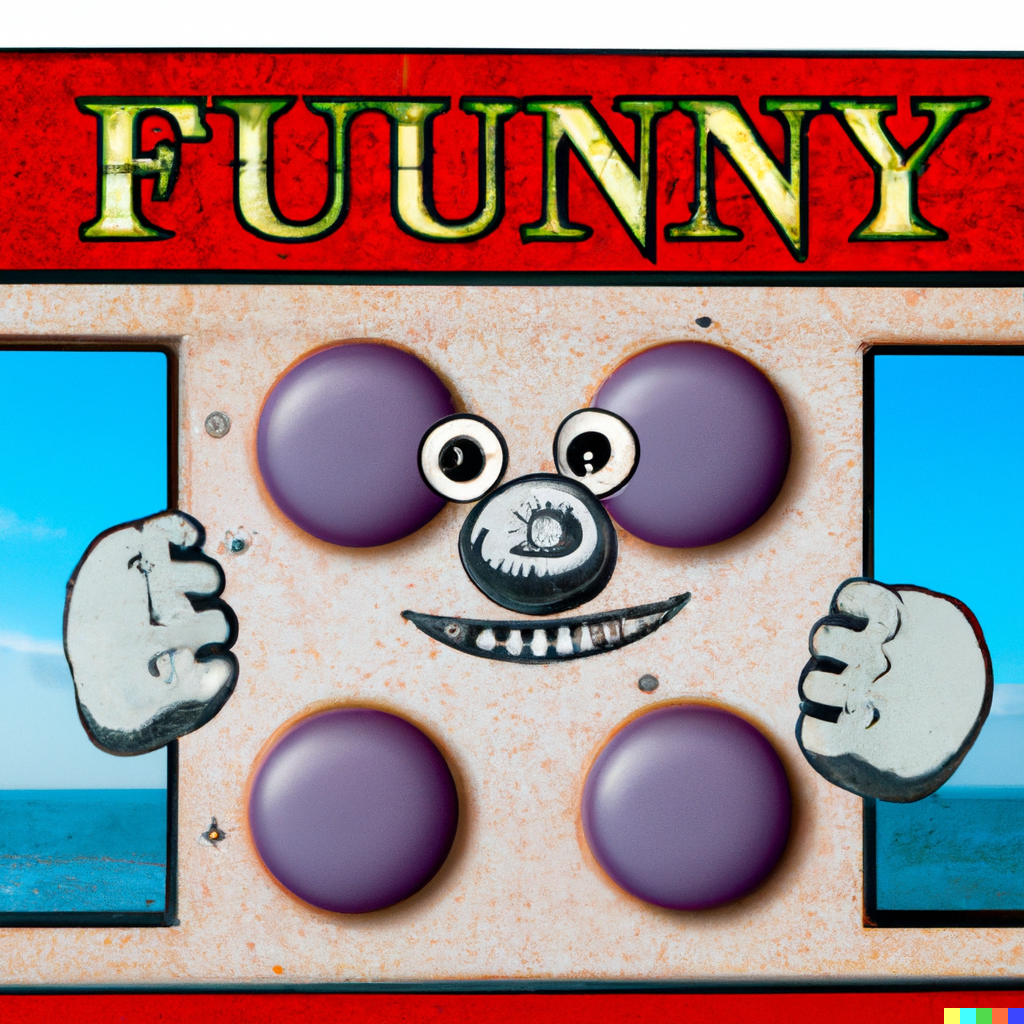

Older AI models

One of the reasons I’ve incorporated the DALL·E 2 aesthetic into this project is that its visual distortions closely mirror the way fun fair imagery evolves over time. Early AI outputs were often unstable: warped text, skewed proportions, colours slipping out of alignment. These qualities aren’t simply glitches — they resemble the cumulative distortions found in hand-painted fairground structures, where repainting, repair and improvisation gradually shift the original design.

This makes DALL·E 2 unexpectedly useful as a tool for thinking about cultural memory. Its inaccuracies and visual drift echo how stories, images and local histories are passed on: not precisely, but through repetition, approximation and reinterpretation. Old fun fair booths and façades at sites like the Rotunda functioned in the same way, carrying traces of multiple makers, seasons and reworkings.

By using DALL·E 2’s now-vanished aesthetic alongside archival references, I’m exploring this overlap between technological misremembering and the informal, evolving nature of seaside visual culture. The aim is not nostalgia, but to understand how distortion, error and inconsistency can be productive methods for examining place, memory and the folk processes that shape them