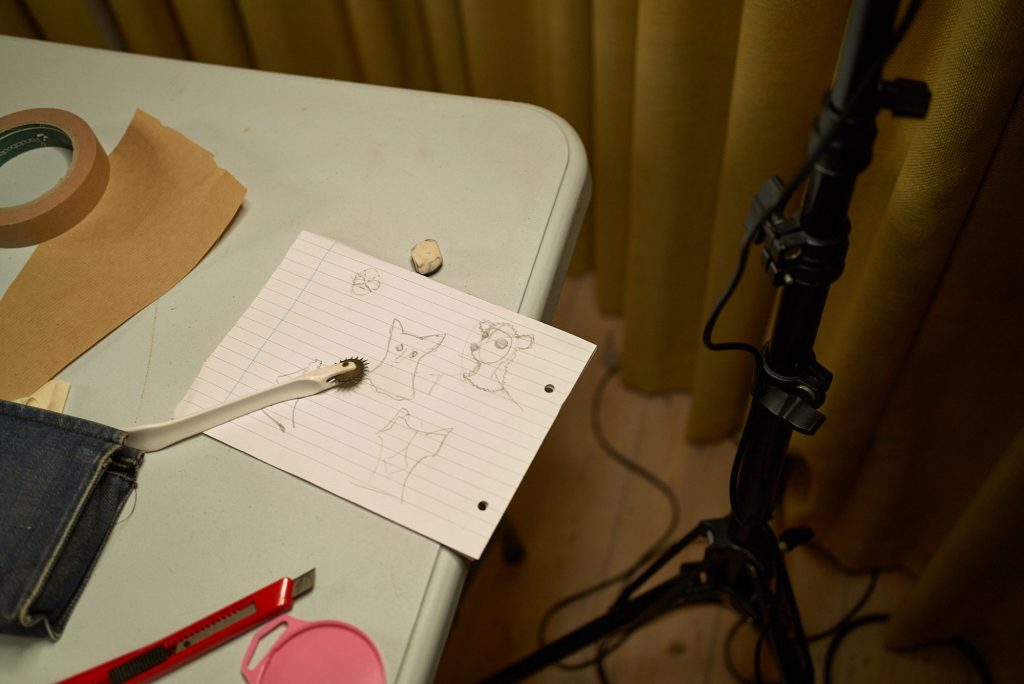

Side Quests Prop Making & Character Development

Alongside the motion experiments, I’ve been developing the props and characters that will feed into the project. A lot of this is about drawing on Kentish traditions – the kind of carnivalesque humour, crude play, and chaotic energy that comes through in things like the old joke shops and the way local carnivals often leaned into parody and grotesque performance.

I’ll also be working with Peter Cocks, who many people will remember from children’s TV in the 90s. He created these brilliantly grotesque characters that used to crash through the studio environment and break the fourth wall with the audience. For a lot of kids from that era, Peter himself became a kind of folkloric figure – part comedy, part chaos, part cultural memory. We’ll be talking more about how that spirit can be distilled and folded into this project, but already his influence gives me a clear sense of tone: exaggerated, playful, and carnivalesque in its mix of humour and unsettling spectacle.

On the physical side, I’ve been collecting materials from building clearances around Folkestone – things salvaged from the old amusement arcades, nightclubs, joke shops, and other remnants of the seaside entertainment industry. These fragments are being translated and distilled into props and talismans, carrying a layered sense of memory and symbolic charge for the virtual production.

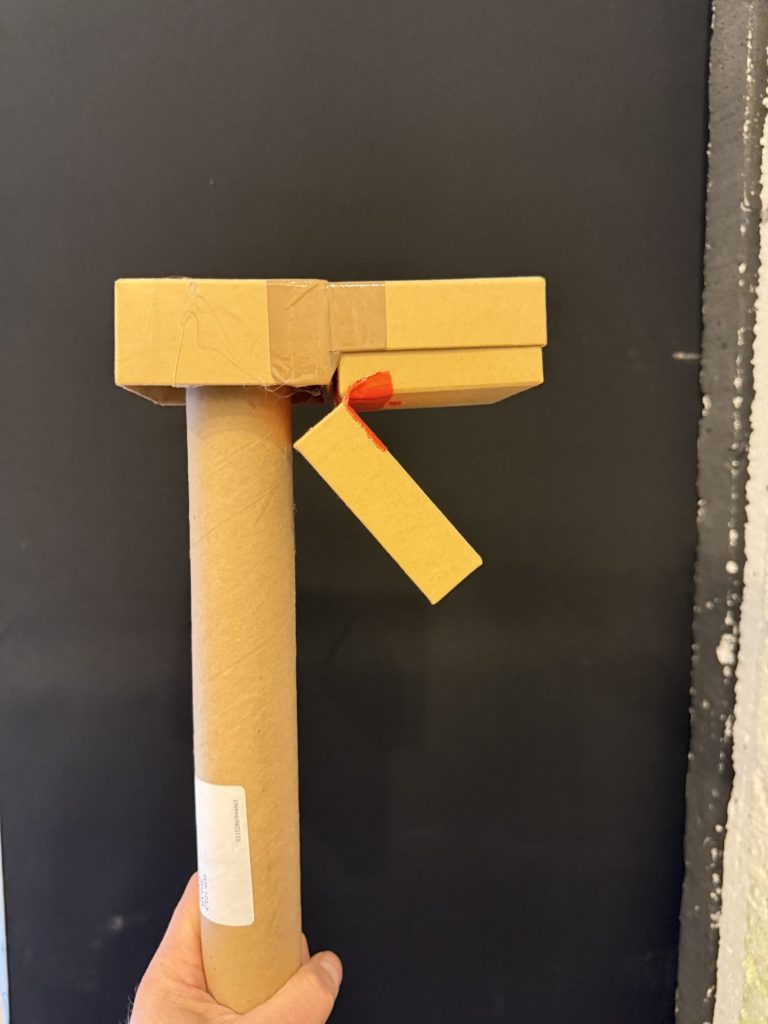

One example is the “nose club”, a piece that plays on both carnival absurdity and talismanic ritual.

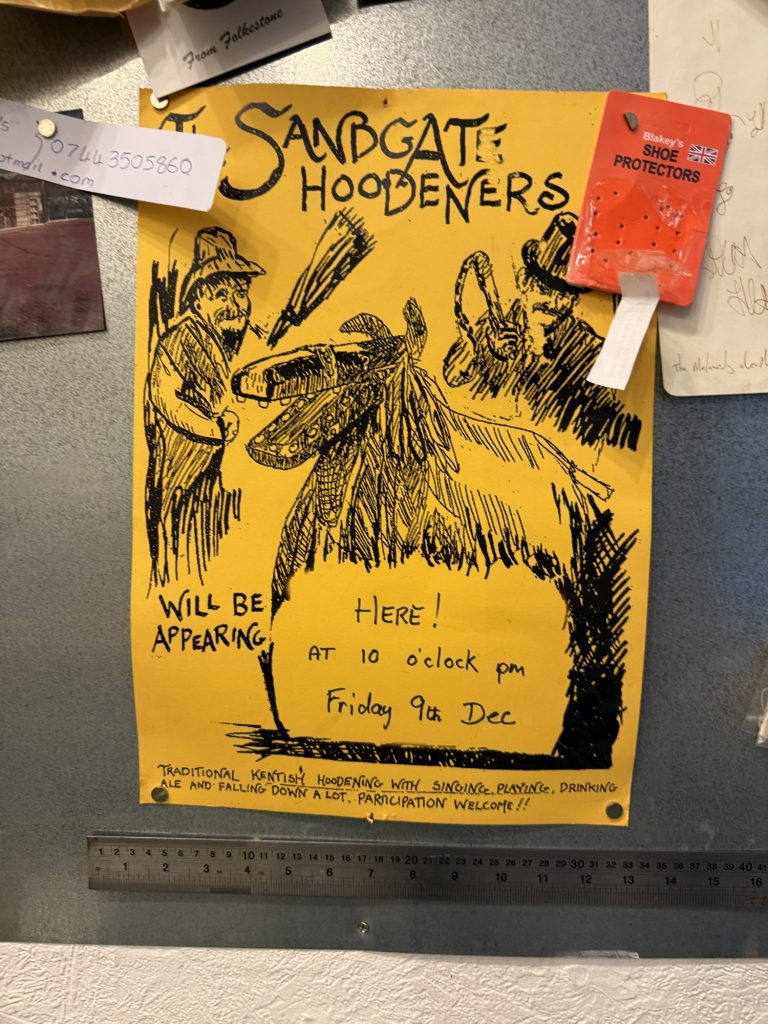

Another is a set of Hooden horses, echoing the East Kent custom where, around Christmas, a wooden horse’s head on a pole would be carried into pubs as part of a raucous, mischievous performance. Traditionally, the Hooden horse was a folkloric visitor, unsettling and comic in equal measure, tied to a provincial vernacular of disguise and misrule. Its grotesque, snapping jaws sit within a wider family of British folkloric horse figures – from the Mari Lwyd in Wales to other carnivalesque beasts that drift through seasonal rituals.

In my version, these Hooden horses have been set onto a wooden frame salvaged from JG’s Amusements, the arcade that once stood at the end of Tontine Street. Adorned with brasses and fragments from the seaside economy, they carry that same uneasy mixture of festivity and menace. In a way, they mirror the grotesque, carnivalesque energy of the seaside entertainment industry itself – the joke shops, arcades, and fairground rides that blur the line between play and excess.

As talismans, they root the project in local folklore while also pushing into the uncanny space of the digital performance environment

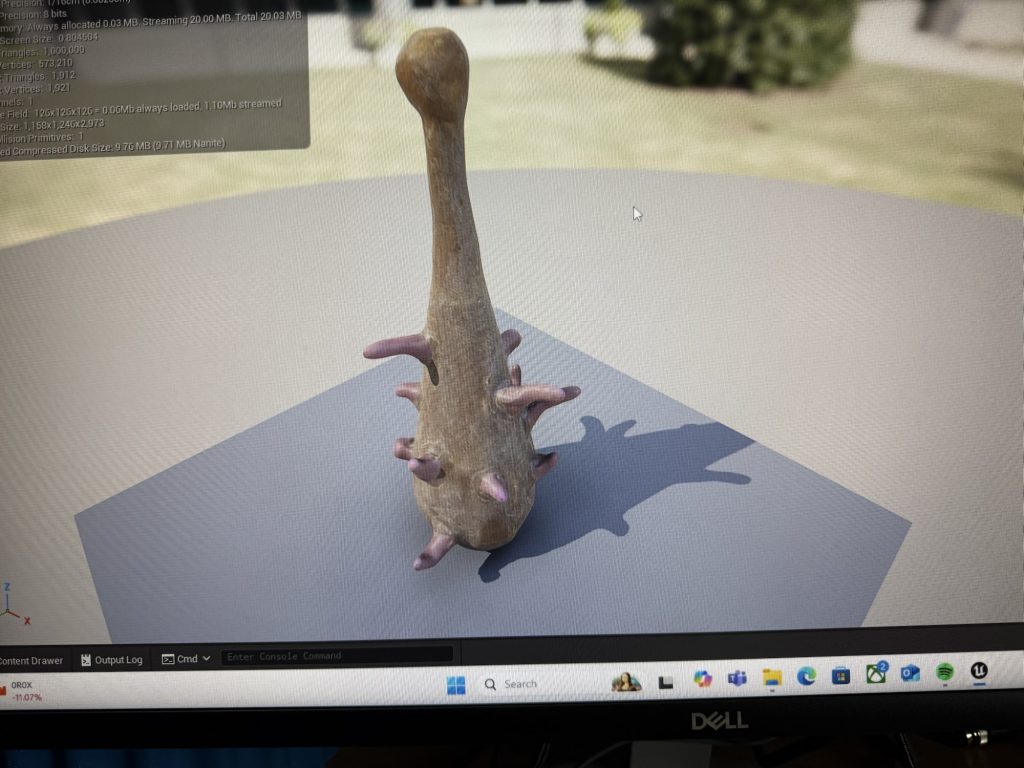

My next beast will be in response to the provincial paintings of 18th century rural England. These distorted beasts often featured oversized Square cows sheep and pigs.

To form the body of the costume i will be using a series of salvaged tongue and groove wooden panels. These were harvested from a mid century Cafe from Tontine Street formally called Eleanor’s Cafe

Eleanor’s café had a fantastic ambience and was a classic mid century Cafe interior.

To realise the forms required I have created a steam bender to allow the processed salvaged wood to be manipulated into a series of curves to form a hooped frame that takes inspiration from obby oss and tourney horses designs.

Working With Anna & Making the Bear

A big part of this project has also been working with Anna Braithwaite. I’ve collaborated with her before, but this year she’s been helping me through my DYCP to build up new skills in fabric construction and pattern cutting. She also runs Folk at the Mariner’s pub, which is where the bear made his first proper appearance, and she was brilliant at helping make sure the character actually worked inside a real folk setting rather than just on paper.

For me, a lot of this is about how the reclaimed wood, the handmade elements, and the performance all build up into something that feels like living folk material — objects with their own stories that can be reactivated by different people and maybe continue beyond this project. I’m also making mummers’ props — shields, swords, crowns — which will later be 3D scanned and used both physically and in virtual experiences. It’s interesting how the technology now feels like it’s supporting the handmade process rather than clashing with it.

Working with Anna on the costume was very collaborative. We talked about those odd, elongated shapes you get in old provincial “square sheep” paintings and how the bear could sit like a slightly off puppet poking out of the frame. The teddy-bear fleece fabric was chosen on purpose: something generic and homemade-looking, more like a 1950s pattern than a recognisable character. The satin lining adds that worn, old-toy feeling — which is what I want the costume to pick up naturally over time.

The hood was the hardest part. We moved towards a simple sculpted snout with ears and rough-cut eyeholes that show Peter’s real eyes. It’s just the right mix of cosy and unsettling. The horse head underneath is deliberately odd too, loosely based on that square-sheep aesthetic, and it’s interchangeable so we can experiment with variations later.

The frame itself has a nice detail — a wooden lip on the inside that gives it a bar-like feel. It almost becomes its own little pub ledge, which suits the character far more than it should. I could imagine hanging horse brasses or rosettes on it. I might refine the harness with leather straps eventually, but I also like the cheap webbing ones. They give it that slightly “lashed together” village-fête look.

Overall, the costume sits in a really satisfying place: not too polished, not too crude, but right in that world of mid-century home sewing and folk-making — the kind of thing someone could have made from a generic pattern, adapted with whatever materials they had. That’s exactly the world this project is building

Bringing the Bear to Life

One of the most interesting things about this project is how much the character changed once we took him out into the real world. We’d done a huge amount of research beforehand — everything from folk traditions and Staffordshire bear figurines to the general chaos of 1980s and 90s children’s TV.

Peter has a notiable career developing and performing in various roles. Particularly relevant are the characters developed for children’s TV below a few videos giving some examples of some of that activity The doctor echoes aspects of mumming plays. Peter embodies the role of the Lord of Misrule Rule in the folkloric world we have been creating.

All of that helped us sketch out who the bear might become, and it certainly fed into Peter’s early performance tests. But none of it compared to what happened when we took the costume into a live folk session at the pub.

The moment Peter walked in as the bear, something shifted. The character suddenly became grumpy, awkward, slightly drunk-looking — with a Sid Vicious sort of stagger and this sense that he couldn’t quite express himself properly. He tried to join in the singing and the dancing, but always at the wrong moment, always interrupting, knocking things off rhythm. It was perfect. The audience reacted instantly: laughing, stepping back, leaning in, not entirely sure what he might do next.

A few photos from the night catch glimpses of this behaviour, but only a fraction. I was in costume too, which helped the performance feel authentic, but it meant I couldn’t capture the really intense, chaotic moments. A lot of the magic simply happened unrecorded.

Afterwards we joked that the bear came across like the “bastard son of Pugsley the Bear and Bungle,” which honestly fits. There’s that unmistakable children’s-TV unruliness in him — the kind of disobedient charm that used to turn up on Saturday morning shows.

But the reaction in the pub made something else very clear: this isn’t just about nostalgia or performance technique. What happened in that room tapped into something older and deeper.

Folk Magic and the Carnivalesque

What really struck me during the performance was how much people enjoyed the disruption. There’s something almost ancient in that response. Folk tradition has always made space for unruly figures — the Hooden Horse, the Fool, the Bear, the Straw Man — characters whose job is to break the normal pattern of behaviour, cause minor chaos, and throw everyone slightly off balance.

Bakhtin’s idea of the carnivalesque describes this well: those moments where everyday order slips, the rules loosen, and the strict edges of society blur. People like that boundary-breaking. There’s a thrill in seeing something that shouldn’t behave properly — behave improperly. A licensed bit of chaos. A moment where anything could happen.

That’s exactly what the bear was doing in the pub. He disrupted the songs, wandered off-beat, annoyed a few people, delighted others, and pushed the whole room slightly off centre. And instead of resisting it, the audience leaned into it. The disorder didn’t feel threatening — it felt alive.

This is the space where folk magic exists: that moment when a character stops being a costume and becomes a real presence, capable of shifting the mood of the room.

Where the Character Finally Made Sense

The live performance confirmed something we’d suspected: the bear only becomes himself when he’s interacting with real people. The costume, the references, the planning — all of that was groundwork. But the actual character emerged only when Peter was face-to-face with an audience who didn’t know what to expect.

That slight chaos, the rule-breaking, the humour, the awkwardness — that’s what brought him to life. And that’s where this project sits best: somewhere between folk ritual, seaside disorder, and that lingering children’s-TV energy where everything is allowed to go just a bit wrong.