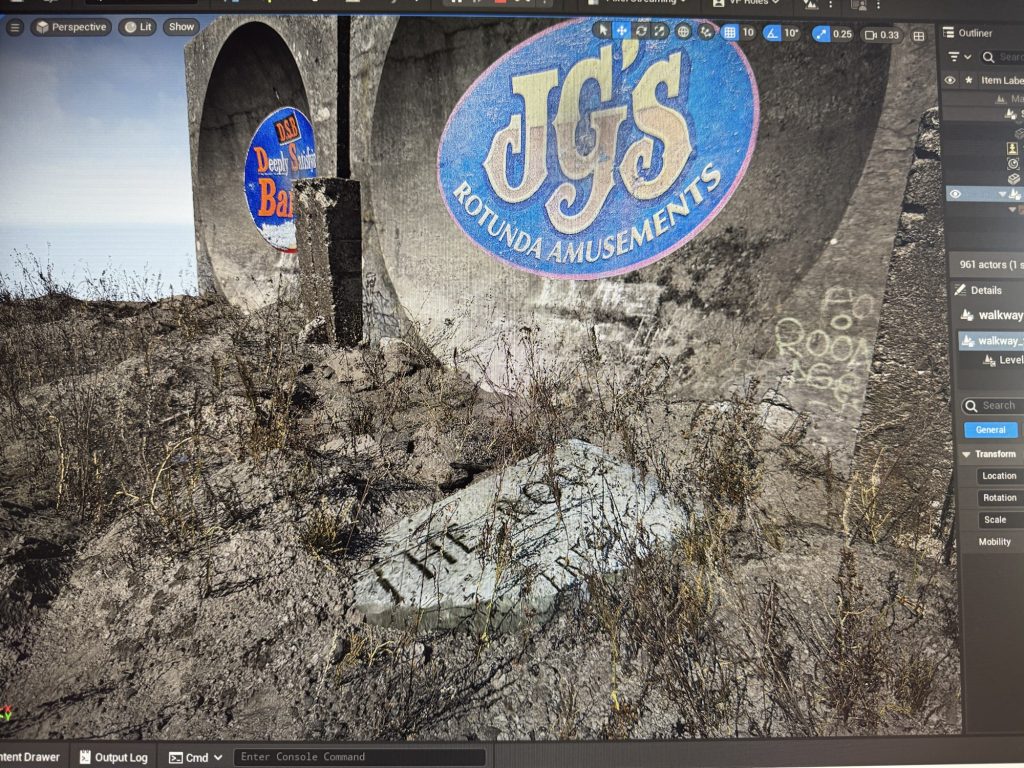

Rotunda Fractured Artefacts

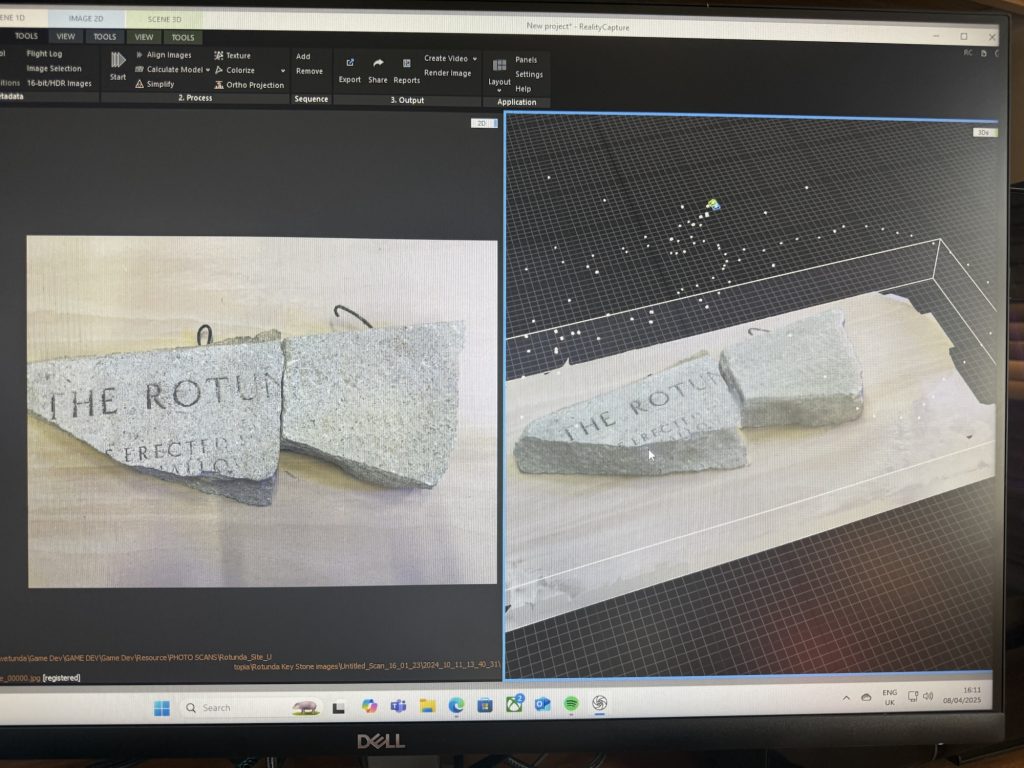

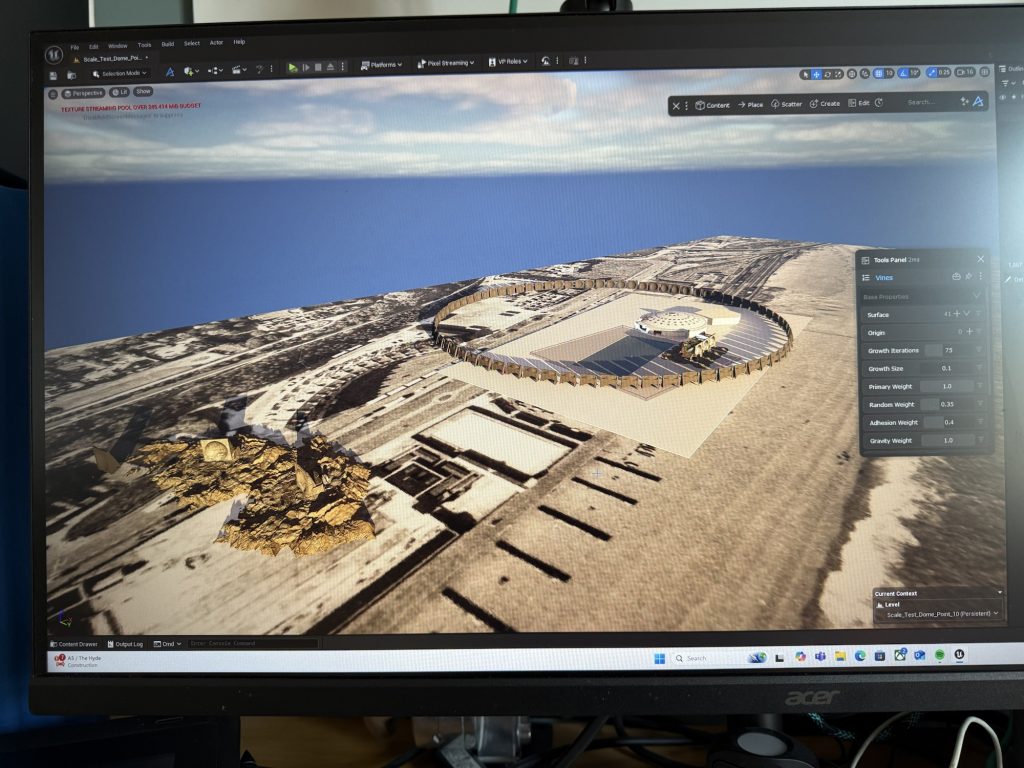

I Recently came across a fragment of the original rotunda dome that was demolished in back in the early 2000’s. This is a great asset for the virtual environment I have been building for the DYCP side quest project.

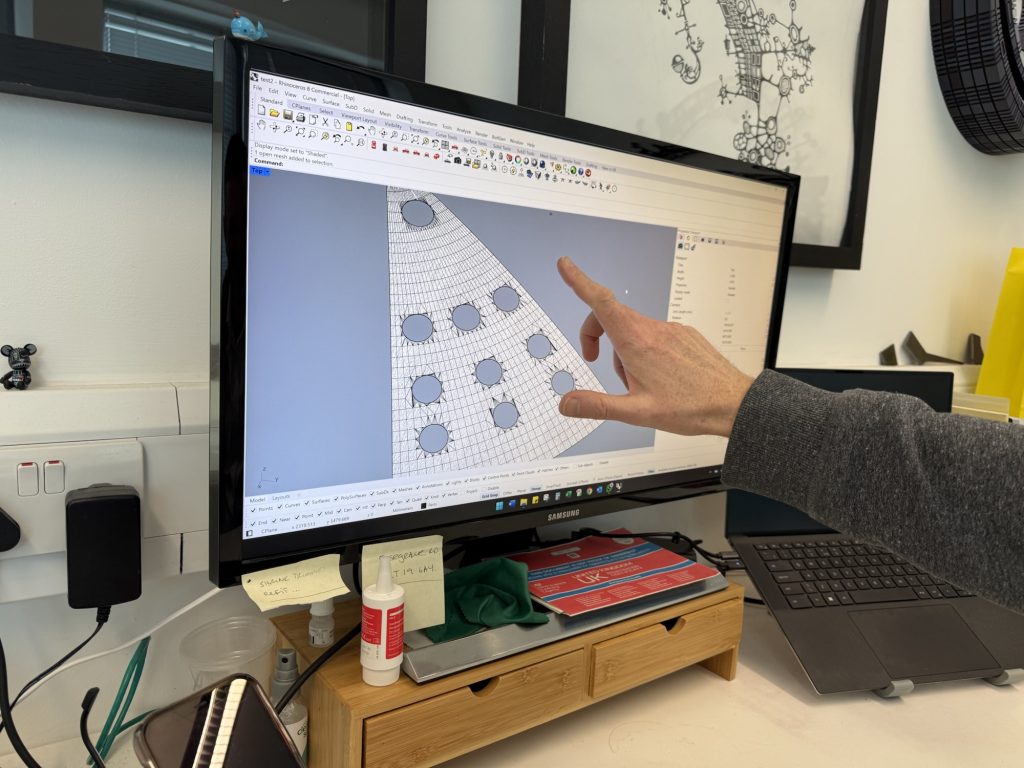

I was lucky enough to be able to utilise a lidar scanning technique on my mobile phone to capture preview scan of the object i then was able to extracted this data image sets to be reconstructed at higher resolution using reality capture a photography software that allows 3-D models to be produced from photographic images. This allow me to capture some of the intangible heritage and traces of recent archaeological fragments of the original rotunda architecture.

Thanks, DR Paul Rennie for sharing the artefacts.

Archival Resources & Historical Reference

Archival materials have become a crucial layer in building the story and atmosphere of this project. I’ve been diving into the History Rooms in Folkestone—formerly housed in the town library and now relocated to Grace Hill, within what’s now called the Folkestone Library – Heritage and Digital Access—which holds a wealth of local studies collections, newspapers, microfilm, and oral history archives (local.kent.gov.uk, news.kent.gov.uk).

The Folkestone Museum’s folklore archive, now based at the Town Hall on Guildhall Street, has also been invaluable, especially for capturing the traditions, old entertainment culture, and objects that shaped the town’s identity (en.wikipedia.org).

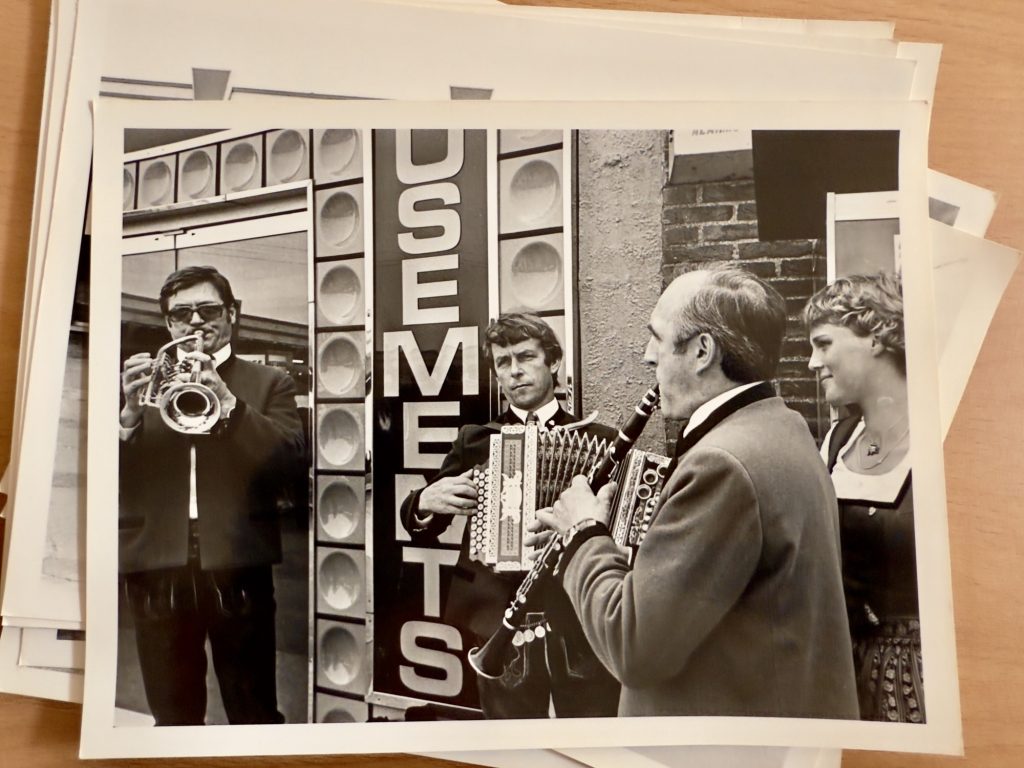

Alongside my own documentation that I’ve been collecting over the years, I realised this simply wasn’t a rich enough perspective to really understand the evolution of the site as a funfair and pleasure space. These archives, with their mixture of official records, ephemera, and oral histories, have given me a deeper sense of how the site shifted in meaning and use across different generations.

Beyond these physical archives, I’ve tapped into digital sources and web communities. Stock photography sites and Flickr have turned up mid-century images of bingo halls, ferry terminals and funfairs that perfectly capture that gritty seaside texture I’m after.

I’ve also found strong support from amateur-historian sites like WarrenPress.net, which offer nostalgic then-and-now perspectives of Folkestone and often shed light on overlooked corners of the town’s history (warrenpress.net).

What’s become increasingly important to me is how these websites themselves—often crude, early-internet creations—are almost archival objects in their own right. Many of them carry the aesthetic of the 1990s or early 2000s: simple HTML layouts, bright or clashing colours, minimal navigation, and a relentless focus on content over polish. They feel hand-built, driven by individual passion rather than institutional curation. This aesthetic is not just a container for historical data but a part of the cultural fabric I’m working with.

Their roughness, their directness, and their user-constructed nature mirror the DIY atmosphere of seaside culture and the funfair itself. For the project, I want to work with some of these stylistic and structural qualities—folding them into how I design environmental interactions—so the experience of the archive isn’t just about what is remembered, but also how it was remembered, shared, and aesthetically framed.